Joda. Det er folk som tror på dette, akkurat som det er folk som trodde Stalin var veien til et bedre samfunn. Det heter ideologi og tradisjonell økonomisk teori (som i likhet med mye samfunnsteori er basert på både forutsetninger og unntak). Bre søk på trickle down economics for å bli litt klokere. Politikere som står for denne økonomiske ideologien har sjelden selv særlig fordeler av dette, i hvert fall i Norge. Jeg tror lite på å tillegge norske politikere skjulte motiver, men at de tar feil av ideologiske årsaker, det tror jeg ofte de gjør. Så du Nytt på Nytt hvor Sanner ble latterliggjort for å avvise en offebntlig utredning ha hadde bestuillt, fordi den ga et svar han ikke likte? Da har man malt seg inn i et hjørne.

Politikk, religion og samfunn President Donald J. Trump - Quo vadis? (Del 2)

- Trådstarter Høvdingen

- Startdato

Diskusjonstråd Se tråd i gallerivisning

-

Joda. Det er folk som tror på dette, akkurat som det er folk som trodde Stalin var veien til et bedre samfunn. Det heter ideologi og tradisjonell økonomisk teori (som i likhet med mye samfunnsteori er basert på både forutsetninger og unntak). Bre søk på trickle down economics for å bli litt klokere. Politikere som står for denne økonomiske ideologien har sjelden selv særlig fordeler av dette, i hvert fall i Norge. Jeg tror lite på å tillegge norske politikere skjulte motiver, men at de tar feil av ideologiske årsaker, det tror jeg ofte de gjør. Så du Nytt på Nytt hvor Sanner ble latterliggjort for å avvise en offebntlig utredning ha hadde bestuillt, fordi den ga et svar han ikke likte? Da har man malt seg inn i et hjørne.

Men denne teorien er jo gammel og historien viser jo entydig at det er fantasi. Hvor faktaresistent skal man være før det mister troverdigheten?Problemet er vel at det ikke er så entydig som du hevder og at økonomiske modeller er noe mindre deterministiske enn de som kreves for å lande en rover på Mars. Jeg tror modellenes entydighet er noe begrenset som sagt, men det er tonnevis av hvisomatte og men involvert. Og det er betydelige elementer av tro involvert som i det meste som er komplisert, men den nåværende regjering (som ikke er de eneste) synes å være i overkant troende på dette området.

Du får sjekke kabeldebattene på HFS vs fysikk teori. Kanskje det gir litt innsikt i faktaresistens?Men denne teorien er jo gammel og historien viser jo entydig at det er fantasi. Hvor faktaresistent skal man være før det mister troverdigheten?For meg virker det veldig som om det for flere of flere er en automatikk i at så fort underliggende mekanismer eller vitenskap innen ett eller annet går over hodet på dem, så tas det som et signal på at man kan tro det man helst vil eller føler for, heller enn å stole på folk som faktisk skjønner ting.

Selv tror jeg ikke jeg har sett noe om «trickle down economics» og «dynamisk skattepolitikk» i noe Høyre-program siden midt på 80-tallet. Den litt Reagan-inspirerte tanken var at kutt i marginalskatten ville skape så mye mer aktivitet at den påfølgende utvidelsen av skattegrunnlaget ville kompensere i statskassen for reduksjonen av skattesatsen. Det viste seg nokså fort at det ikke var slik, så den idéen ble begravd i stillhet.Og det er betydelige elementer av tro involvert som i det meste som er komplisert, men den nåværende regjering (som ikke er de eneste) synes å være i overkant troende på dette området.

Den meget omtalte «nordiske modellen» er basert på det motsatte prinsippet, at velferdsordninger skal være tilgjengelige for alle. Ikke som utdeling av almisser til de verdige trengende, men et universelt tilbud. Da har de fleste noe penger mellom hendene, og det er mange hender tilgjengelige i arbeidsmarkedet. Da kan man tjene riktig gode penger på å selge Grandiosa til folket - «trickle up». Dessuten gjør det sosiale sikkerhetsnettet at fallhøyden ved omstilling og nyetablering er forholdsvis liten. Man ender stort sett ikke opp som hjemløs uten helseforsikring om en fabrikk stenger. Det gir en omstillingsevne og effektivitet som også hjelper ganske bra på inntjeningen.Sist redigert:Selv tror jeg ikke jeg har sett noe om «trickle down economics» og «dynamisk skattepolitikk» i noe Høyre-program siden midt på 80-tallet. Den litt Reagan-inspirerte tanken var at kutt i marginalskatten ville skape så mye mer aktivitet at den påfølgende utvidelsen av skattegrunnlaget ville kompensere i statskassen for reduksjonen av skattesatsen. Det viste seg nokså fort at det ikke var slik, så den idéen ble begravd i stillhet.

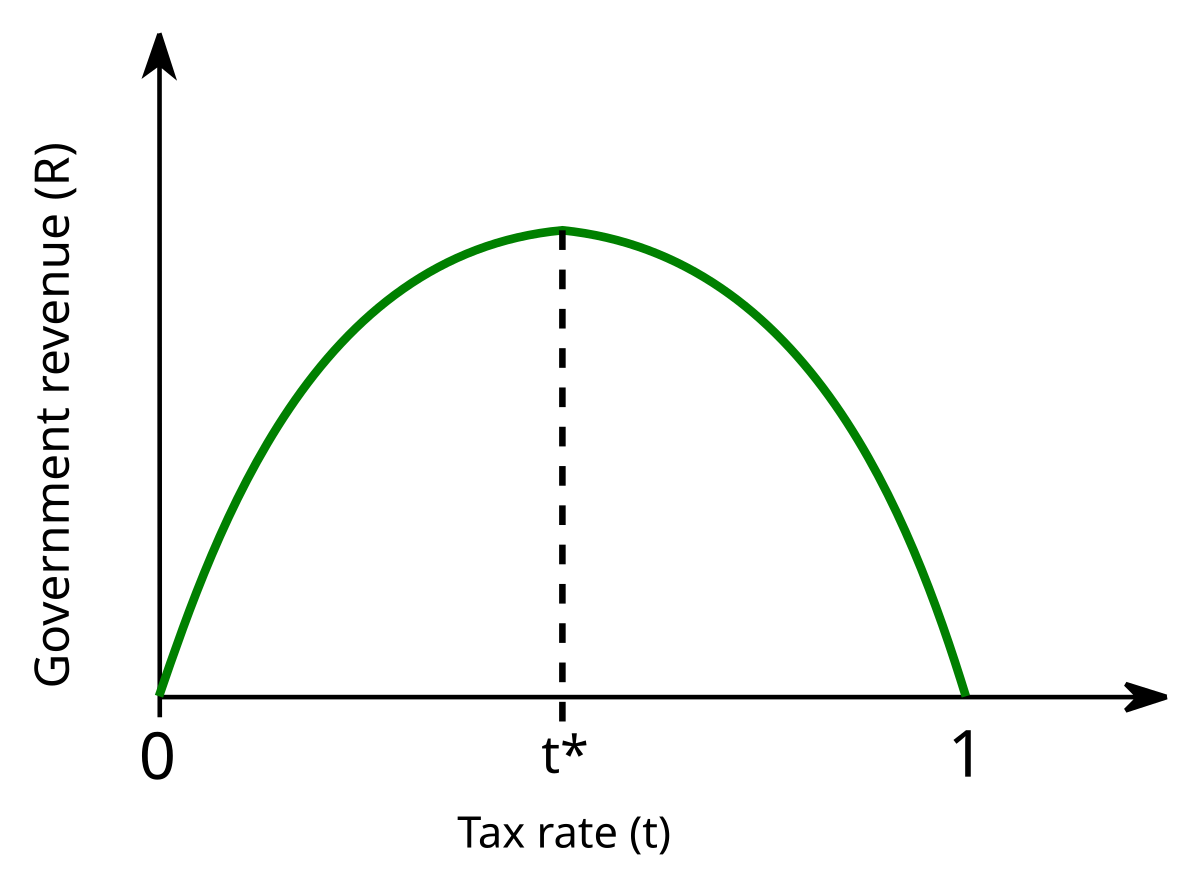

Laffer curve - Wikipedia

en.m.wikipedia.org

en.m.wikipedia.org

Mvh

KJJa, jeg kjenner til den. Den er forsåvidt riktig, men det er vanskelig å bedømme formen på kurven og hvor man befinner seg på den. Ytterpunktene er opplagte: Ved 0 % skatt blir det ingen skatteinntekter. Ved 100 % skatt blir det heller ingen skatteinntekter, for ingen vil gidde å gjøre noe som helst av «hvit» økonomisk aktivitet. Et sted mellom er det et optimum, en skattesats som maksimerer statens inntekter ved å balansere skatteprosent mot bivirkninger.

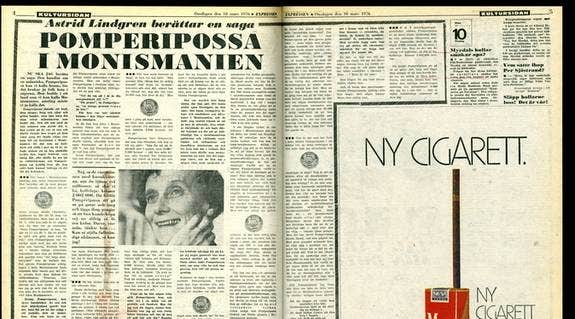

Laffer-kurven tegnes ofte symmetrisk, slik at den «optimale» skatteprosenten ser ut til å være et sted rundt 50 %, men det kan tenkes at det ligger noe høyere. 1970-tallets marginalskatter på 80-85 % var nok et godt stykke over optimum. Astrid Lindgren betalte 102 % et år og ble såpass eitrende forbanna at det kostet finansministeren jobben.

Pomperipossa i Monismanien

I sagans form beskrev Astrid Lindgren hur hon som egenföretagare tvingades betala 102 procent i skatt. Läs hela det berömda debattinlägget här.www.expressen.se

Dagens tulling:

Police Officer Arrested After Posting Video of Himself Charging Police Lines During Capitol Riots.

A Pennsylvania police officer was arrested on Friday for his role in the Jan. 6 riots at the U.S. Capitol Complex after posting videos of himself charging police lines.lawandcrime.com

Dagens tulling:

Police Officer Arrested After Posting Video of Himself Charging Police Lines During Capitol Riots.

A Pennsylvania police officer was arrested on Friday for his role in the Jan. 6 riots at the U.S. Capitol Complex after posting videos of himself charging police lines.lawandcrime.com

Ja han trenger ikke ny jobb på mange år...Denne merkelige troen på at en hver formuesøkning fører til arbeidsplasser synes jeg er snodig. Ja, i en del tilfeller gjør den det. Og i andre tilfeller fører den til flere arbeidsplasser eller større formuer utenlands, eller rett og slett prisdrivende investeringer i luksusboliger eller utleieleiligheter innenlands. Som alle økonomiske tiltak må det målrettes dersom det skal få ønskete effekter. Jeg er helt enig i Asbjørns innlegg 12.232, men synes ikke det går langt nok. Og skulle også ønske hans parti hadde vett nok til å tilslutte seg det han sier. Men dessverre synes det å ha festet seg et slags mantra om at enhver avgifts- eller skattereduksjon er av det gode. FrP er for øvrig verstingen her.

Og dette bildet har endret seg mye til det verre med den skaleringen man kan få til over www. Produksjonskostnadene er tilnærmet null for heldigitale virksomheter. Så korrelasjonen mellom formuesbygging og jobbskaping er svakere enn den har vært noensinne. Så forskjellene øker.- Ble medlem

- 24.08.2018

- Innlegg

- 4.819

- Antall liker

- 3.163

Hvordan er produksjonskostnadene tilnærmet 0 for digitale virksomheter?Det er like dyrt å lage en musikkfil som blir kjøpt av en kunde som en som blir kjøpt av en million. Så formuleringen er ikke helt presis, men det er derfor det refereres til skalering. Stordriftsfordelene er enorme.Kanskje vel så viktig: Den fysiske verdikjeden forsvinner. Den var pressing av plater, trykking av cover, montering, lagring, transport, butikksalg. Der var det mange hender involvert uten spesielle krav til utdannelse, men jobben måtte gjøres på bestemte steder for å få produktet frem til kundens hender.

Kompetanseprofilen for å drifte en streamingtjeneste eller nedlastingstjeneste er en helt annen, jobben kan gjøres fra hvor som helst i verden, og det blir ikke mer eller mindre jobb om en sang streames en million ganger enn om den ikke selger. Hele greia kan utføres fra Bangalore eller Mauritius, og brukeren merker ingen forskjell.

Klart det gjør noe med arbeidsmarkedet.The Capitol rioters speak just like the Islamist terrorists I reported on

The similarities between domestic and Islamist terror groups are hard to avoid. Followers of both are drawn to a cause greater than themselves that gives them a shared identity and a mission to correct perceived wrongs, by whatever means necessary. At the core of this cause is a profound sense of victimization and humiliation. The terrorists I met from Afghanistan, Somalia, Saudi Arabia and West London all believed that their pride and purpose had been stolen from them — by, in their case, the United States and its allies — and so were drawn to a movement that promised to restore that pride and purpose, even by violence. Today’s American extremists think (because they’ve been told by the former president and other leaders) the system is rigged against them and is bent on dismantling everything they believe in.

For both groups, their sense of oppression is built on fantasy. I interviewed many Islamist terrorists with middle-class upbringings, steady jobs and graduate degrees. Among the rioters who assaulted the U.S. Capitol were doctors, business owners and real estate agents — more victors than victims of the system. “The militants often experience their humiliations vicariously — ‘our religion is supposedly under attack’ for the jihadis, ‘our race is purportedly under attack’ for the Proud Boys,” says Peter Bergen, who has written and reported on terrorism for more than 20 years. “It feeds into a sense of grievance that they then feel they need to act upon, even though it’s not like they themselves have suffered personally.”

Så får vi se hvilke konsekvenser det får for radikaliseringsimamene deres.In July 2016, during a presidential campaign marked by Donald Trump’s already aggressive attacks on government, I asked then-Director of National Intelligence James Clapper if he ever applied the intelligence community’s metrics for failed states to the United States. “If you apply those same measures against us, we are starting to exhibit some of them, too,” he told me. “We pride ourselves on the institutions that have evolved over hundreds of years, and I do worry about the . . . fragility of those institutions.” He described “legal institutions, the rule of law, protection of citizens’ liberty, privacy” as “under assault.”

Five years later, Clapper tells me he sees those same trends worsening. “I wish it wasn’t true, but it is hard not to objectively observe those trends are continuing,” he said. “We have armed fanatic mobs attacking the seat of our democracy. This is what happens in unstable counties.”

Merrick Garland says that as attorney general he will fight discrimination, domestic terrorism

Roger Stone, Alex Jones Under Federal Investigation for Ties to Capitol Rioters: Report

The DOJ and FBI are reportedly investigating the role Jones and Stone played in the Jan. 6 riots at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C.lawandcrime.com

Before becoming a judge, Garland was best known in legal circles for his role guiding the investigation and prosecution of Timothy McVeigh, the man who detonated a bomb outside a federal building in Oklahoma City in 1995, killing 168 people. McVeigh was convicted and sentenced to death, and in 2001 he was executed.

På tide for både tullinger og klovner å bli veldig, veldig bekymret.In his prepared remarks, Garland also highlighted how his experience handling domestic terrorism is particularly relevant now.

“From 1995 to 1997, I supervised the prosecution of the perpetrators of the bombing of the Oklahoma City federal building, who sought to spark a revolution that would topple the federal government. If confirmed, I will supervise the prosecution of white supremacists and others who stormed the Capitol on January 6 — a heinous attack that sought to disrupt a cornerstone of our democracy: the peaceful transfer of power to a newly elected government.”Sist redigert:UUtgatt24668

Gjest

I UK har de formueskatt og mva på større selskaper og formuer men ikke på den lokale butikken eller små familiedrevne hoteller etc. det kan ha en viktig effekt på mindre selskaper. Viktig å ta med i regningen.Joda. Det er folk som tror på dette, akkurat som det er folk som trodde Stalin var veien til et bedre samfunn. Det heter ideologi og tradisjonell økonomisk teori (som i likhet med mye samfunnsteori er basert på både forutsetninger og unntak). Bre søk på trickle down economics for å bli litt klokere. Politikere som står for denne økonomiske ideologien har sjelden selv særlig fordeler av dette, i hvert fall i Norge. Jeg tror lite på å tillegge norske politikere skjulte motiver, men at de tar feil av ideologiske årsaker, det tror jeg ofte de gjør. Så du Nytt på Nytt hvor Sanner ble latterliggjort for å avvise en offebntlig utredning ha hadde bestuillt, fordi den ga et svar han ikke likte? Da har man malt seg inn i et hjørne.Only 4% say the impeachment trial made them less supportive of Trump; 42% say it made them more supportive. Fifty-four percent say it didn't affect their support.

[…]

Asked to describe what happened during the assault on the Capitol, 58% of Trump voters call it "mostly an antifa-inspired attack that only involved a few Trump supporters." That's more than double the 28% who call it "a rally of Trump supporters, some of whom attacked the Capitol." Four percent call it "an attempted coup inspired by President Trump."

[…]

Three of four, 73%, say Biden wasn't legitimately elected. Most don't want their representatives to cooperate with him, even if that means gridlock in Washington.

Exclusive: Defeated and impeached, Trump still commands the loyalty of the GOP's voters

In a new Suffolk/USA TODAY Poll, Trump voters said 46%-27% that they would abandon the GOP and join a third party\u00a0if Trump decided to create one. eu.usatoday.com

eu.usatoday.com

er det liv etter trump?Det spørs. Hvis de mange etterforskningene bærer frukt og han ender i fengsel, så kanskje, over tid, men uansett vil nok et stort flertall se dette som et komplott i regi av den dype staten og fortsette å se ham som selve frelseren og Biden som illegitim.

At splittelsen som nå eksisterer kan leges på mindre enn minst et par mannsaldre har jeg ingen tro på. At det faktisk vil skje har jeg enda mindre tro på. En økende polarisering (om det nå er mulig) og et fortsatt sakte (eller ikke så sakte) forfall mot status som en feilet stat er langt mer sannsynlig. Tror jeg.jeg er vel ikke mer optimistisk enn jmm, men om det skulle bli mindre splittelse, så bare gjennom praktisk politikk (som endrer hverdagen), og ikke retorikk. hadde de gått hardt ut og sprengt til himmels alle «monopolene», dvs. kjørt antitrust radikalt, så var i det minste noen gjort. som frank sa i en av lenkene jeg la ut; det er én mann som kan hjelpe deler av den gjengen som følger trump og det er han mr antitrust.

Banana, your republic is here.Only 4% say the impeachment trial made them less supportive of Trump; 42% say it made them more supportive. Fifty-four percent say it didn't affect their support.

ja, det er spinnvilt. og det fins ikke det seminar på kloden som kan gjøre noe med det (tror jeg). bare politikk som endrer virkeligheten, for synapsene er tydeligvis i vranglås. en kan bli materialist (i politisk betydning) av mindre.Banana, your republic is here.

Family of 11-Year-Old Boy Who Died Amid Texas Blackouts Suing Electrical Grid Operator That Has Sovereign Immunity

The private electric grid operator ERCOT has sovereign immunity, but this is not stopping some Texans from suing them amid the devastating winter blackouts. Case in point, there is the family of 11-year-old Conroe boy Christian Pavon. They said they found him dead on Tuesday after their mobile...lawandcrime.com

Hvordan i h...e kan en privat nettoperatør ha «sovereign immunity»???

Sovereign immunity - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

Fordi de eier politikerne?noe nesten som dette?

en.wikipedia.org

Fordi de eier politikerne?noe nesten som dette?

As COVID was breaking out in New York state last March, Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed an infamous executive order requiring nursing homes to accept patients who were presumed to have the virus. Following the order, about 9,000 COVID patients were brought into nursing homes across the state, likely leading to the virus’s rampant spread in those facilities.

But instead of correcting for his mistake, Gov. Cuomo listened to the demands of one of his top donors — the lobbying group for the nursing home industry. As The Daily Poster reported back in May, he granted full corporate legal immunity to nursing homes, all the way up to the c-suite. At the time, New York Democratic Assemblyman Ron Kim sounded an alarm, warning that the liability protections removed a key deterrent to corporate misbehavior and effectively shielded nursing home executives from legal consequences if their cost-cutting, profit-maximizing decisions endangered lives.

The Legislator Facing Cuomo’s Wrath

A Q&A with Ron Kim, the Democratic lawmaker facing threats of retribution for spotlighting the New York governor’s move to shield nursing home execs from consequences. www.dailyposter.com

www.dailyposter.com

Tydeligvis. Perfekt oppsett for å unngå å bli holdt ansvarlig: Organisert som en privat stiftelse med styremedlemmer oppnevnt av industrien (og slipper dermed å bli holdt politisk ansvarlig), men samme beskyttelse mot søksmål som hvis man var en statlig funksjon (og slipper dermed å bli holdt rettslig ansvarlig). Noe trumpsk over den der.Fordi de eier politikerne?

Can ERCOT be held accountable for its errors?

The Texas Supreme Court isconsidering whether ERCOT, a private, nonprofit corporation, is...www.houstonchronicle.com

ERCOT was in trouble from almost the very beginning of deregulation. Five ERCOT employees, including the chief information officer and director of information technology, went to prison in 2006 and 2007 over a $2 million fake billing scheme for security services that included paying the wages of non-existent employees, including a dead man.

The scandal, triggered by suspicious ERCOT employees who alerted the Public Utility Commission, shined a light on the lack of transparency at ERCOT, which had fought outside audits and sought to uncover the identity of the whistleblowers.

Ja, her kommer de opp som «Fjaellbacka Man In Tears», «25-Year-Old From Fjaellbacka» osv. Skjæbnen kan tydeligvis være lunefull overalt hvor det finnes en IP-adresse.@Asbjørn Det var minst like interessant å se hvilke artikler som lå klare for meg nedenfor artikkelen. Mange spektakulære skjebner i Stavanger som jeg aldri har hørt om. Click-bate deluxe.

Jeg forstår heller ikke helt hvorfor det står en annonse for «Bästsäljande japanske plåster» like under boksen hvor jeg taster inn dette på HFS, men det ser i det minste ut til at jeg er kvitt annonsene for «Alla Traktorer Ur Konkursbon» som forfulgte meg i lengre tid.

Jeg tenker at jo mer irrelevante og absurd malplasserte annonser jeg ser, desto sikrere kan jeg være på at mine små forsøk på å bekjempe tracking cookies fungerer.

Jeg har ikke så sans for TYT, de er litt for anti-Trump, men dette var skremmende. Hvorfor er ikke denne filmen sendt i alle kanaler i alle land?Denne er virkelig verd å se:

Lurer på om dette kom på Fox News eller noen av de andre Il Drumpft vennlige kanalene?Must hurt

Demokratene slåss mot en religiøs bevegelse. Sunn fornuft, fakta og vitenskap kan de bare glemme. Disse er resitente mot det! Det viser vel våre egne minons her inne. Som sagt før, tror man på en løgn som ikke kan bevises, så er det veldig lett å tro på en til og ikke et argument i verden kan endre det!ja, det er spinnvilt. og det fins ikke det seminar på kloden som kan gjøre noe med det (tror jeg). bare politikk som endrer virkeligheten, for synapsene er tydeligvis i vranglås. en kan bli materialist (i politisk betydning) av mindre.

Her må det en massiv informasjonskampanje om Trump og hans virkemåte på plass, som denne filmen som tidligere er nevnt. Det er det eneste som virker.

Jeg lurer på hva annet som finnes, som ikke er vist på grunn av mulige søksmål?Hjelper vel ikke mye med slike filmer heller.... det er jo bare Fake News fra media...... mot rotfestet dumhet og dårskap hjelper egentlig ingenting...

Jeg hører hva du sier og jeg er egentlig enig, men det kan jo bare ikke være sånn. Da er vi fucked! Noenganger skulle jeg ønske jeg hadde den samme egenskapen, putte noe ørene og bruke så svarte briller at jeg hverken ser og hører annet enn jeg vil se og høre...Hjelper vel ikke mye med slike filmer heller.... det er jo bare Fake News fra media...... mot rotfestet dumhet og dårskap hjelper egentlig ingenting...fra den andre siden:

His press conference performances notwithstanding, the facts and evidence show that Cuomo is not someone who cares much about facts and evidence. But his liberal supporters don’t care: A Siena College polltaken after the nursing home scandal broke found that 83 percent of New York Democrats still approve of Cuomo’s handling of COVID, with more than 80 percent also saying specifically that they approve of his work “communicating with the people of New York” and “providing accurate information.” To hammer home the cognitive dissonance, only 54 percent said he’d done a good job “making public all data about COVID-related deaths of nursing home patients,” which suggests both that 54 percent of New York Democrats are full of it and that a significant portion of the rest of them know Cuomo is full of it but don’t care. To many voters, celebrating the idea of the competent blue-state governor is more important than reckoning with the reality of a serially underachieving chief executive playing three-card monte with dead bodies. At this point, Andrew Cuomo could probably shoot someone on Fifth Avenue and get away with it.

Why Do Democrats Pretend Andrew Cuomo Did a Good Job With COVID?

Andrew Cuomo's apparent cover-up of nursing home deaths is yet more mismanagement for his forgiving public to forgive.slate.com

Blir fun

Supreme Court Denies Donald Trump a Stay in Manhattan DA’s Case for Financial Records

The Supreme Court of the United States on Monday, Feb. 22, denied Donald Trump a stay in Manhattan District Attorney Cy Vance's case for the former president's financial records.lawandcrime.com

Livlig dag i Høyesterett. Trump tapte også sju forskjellige søksmål om valgresultatet i samme slengen, hvor hans egenhendig utnevnte dommere stemte mot ham.

It Was an Explosive Morning for Supreme Court Orders — Here’s What You Missed

The court elected to dispense with culture war hallmarks of the past four years that radiated through cable news as evidence of distinctly Trumpian division.lawandcrime.com

The highest court in the land’s giveth and taketh away dance continued in perhaps the issue nearest the former president’s heart—never substantiated claims of electoral fraud during the 2020 presidential election. Seven total challenges were rejected. Those rejections concerned lawsuits aimed at overturning President Joe Biden’s wins in Georgia, Arizona, Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania. Three of the seven dismissed challenges were filed in Pennsylvania alone but only one of those lawsuits resulted in any public discussion.“This Supreme Court action once and for all ends these frivolous election cases,” the City of Detroit’s lead counsel David Fink told Law&Crime. “Every claim of election fraud in Michigan has been rejected. It’s time for the attorneys who filed these baseless lawsuits to be held accountable for their actions.”- Ble medlem

- 28.09.2016

- Innlegg

- 13.105

- Antall liker

- 14.715

Axios: - Jeg bestemmer fortsatt

Ekspresident Donald Trump er ventet å holde sin første tale siden han forlot Det hvite hus førstkommende søndag. - Jeg bestemmer fortsatt, er Trumps budskap i talen ifølge nettstedet Axios. www.dagbladet.no

www.dagbladet.no

Hvor lenge, og hvor åpenbart kan et menneske være i en maktposisjon, samtidig som de i all offentlighet demonstrerer grunnsetningene i læreboka for sosiopatisk paranoia, før menn i hvite frakker tar affære? -

Laster inn…

Diskusjonstråd Se tråd i gallerivisning

-

-

Laster inn…