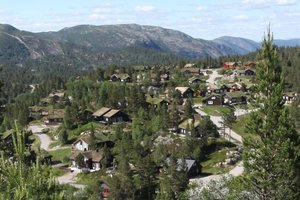

When catastrophic fires occur, experts often blame the so-called wildland-urban interface, the vulnerable region on the perimeter of cities and suburbs where an abundance of vegetation in rugged terrain is susceptible to burning.

Yet the fire disasters that we’re seeing today are less wildland fires than urban fires, Cohen said. Shifting this understanding could lead to more effective prevention strategies.

“The assumption is continually made that it’s the big flames” that cause widespread community destruction, he said, “and yet the wildfire actually only initiates community ignitions largely with lofted burning embers.”

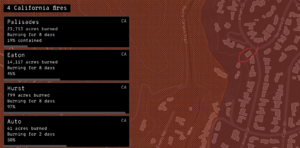

Experts attribute widespread devastation to wind-driven embers igniting spot fires two to three miles ahead of the established fire.

Maps of the Eaton fire show seemingly random ignitions across Altadena.

“When you study the destruction in Pacific Palisades and Altadena, note what didn’t burn — unconsumed tree canopies adjacent to totally destroyed homes,” he said. “The sequence of destruction is commonly assumed to occur in some kind of organized spreading flame front — a tsunami of super-heated gases — but it doesn’t happen that way.

“In high-density development, scattered burning homes spread to their neighbors and so on. Ignitions downwind and across streets are typically from showers of burning embers from burning structures.”