Da får de stenge alle pol i hele landet daStengte pol i noen kommuner medfører økt trafikk til nabokommuner som har åpne pol. Et stengt Nille eller Cubus medfører ikke samme mobilitet. Helt logisk for alle som er nogenlunde oppegående

Medisin og helse Corona

- Trådstarter Disqutabel

- Startdato

Diskusjonstråd Se tråd i gallerivisning

-

- Ble medlem

- 19.09.2014

- Innlegg

- 23.524

- Antall liker

- 16.422

Pøh, da har man jo leid inn noen til å stø i kø for seg.Det der minner om et slipp av eksklusive viner fra Burgunder.Nok kos.

Den skjøre tilliten

Både Høies hyttetur, vinglingen om alkohol og åpningen for verdenscup i Norge er problematiske. www.dagbladet.no

www.dagbladet.no

Når hele landet lever under strenge tiltak, og østlandet er bortimot hermetisk lukket, forventes intet annet enn gullstandar fra ministre.Sist redigert:

NettoppPøh, da har man jo leid inn noen til å stø i kø for seg.

Covid: Police and protesters clash during Dutch curfew demo

Police used water cannon and tear gas to clear protesters in Eindhoven opposed to a new curfew. www.bbc.com

www.bbc.com

Det kan nok bli mer av dette rundt i Europa fremover.Polet forts....

Erna ser på dette og sikler.

Covid: Police and protesters clash during Dutch curfew demo

Police used water cannon and tear gas to clear protesters in Eindhoven opposed to a new curfew. www.bbc.com

www.bbc.com

Det kan nok bli mer av dette rundt i Europa fremover.

Kvifor det?Da får de stenge alle pol i hele landet da

Regjeringen bekrefter: Eldre og helsearbeidere blir prioritert i polkø (NRK SATIRIKS)

Frykter at polet blir overbelastet. www.nrk.no

www.nrk.no

Mandag morgen gjenåpnes Vinmonopolet i Oslo og Follo-regionen. Regjeringen mener det er viktig å sikre tilgang på alkohol til de svakeste gruppene.

– Eldre og syke får stå først i polkøen. Helsearbeidere blir også prioritert, slik at de svake har noen å drikke med, forklarer helseminister Bent Høie.

Jobbes på spreng

Han forsikrer om at det nå jobbes på spreng for å bygge ut polkapasiteten over hele landet.

– Det verste som kan skje, er at polet blir overbelastet. Får de ansatte for mye å gjøre, kan det føre til feilanbefalinger av vin til maten, advarer han.

Skoler og gymsaler blir tatt i bruk for å lage midlertidige nødpol. De neste dagene blir også sivilforsvaret satt inn for å anbefale viner til hjemmekontor.

Hedrer heltene

I Follo har beboere stått i vinduene og applaudert de ansatte på Vinmonopolet i hele dag. Barna på hjemmeskole har tegnet tegninger av drinker i regnbuefarger for å hedre heltene på polet.

– Det er viktig med åpne vinmonopol i en sånn fase som Oslo-regionen befinner seg i. Vi vet for eksempel at det er liten sjanse for at Oslo-borgere drar på hytta når de er dritings i egen bolig, sier assisterende helsedirektør Espen Nakstad.

Mutasjoner

– Dessuten frykter vi mutasjoner. For eksempel at polkøen i Bærum går over til å bli angrepillekø.

Folkehelseinstituttet anbefaler alle nordmenn å laste ned den nye korona-appen som skal gjøre det lettere å spore opp nærmeste vinmonopol.

Bare et fattig forsøk fra min side på å finne en logisk tråd i det som skjer for tidenKvifor det?Hvorfor er det tryggere for kåråna inne på polet i forhold til i andre butikker

Hvorfor kan polet være oppe når feks andre små enkeltstående butikker med lite å gå på økonomisk må stenge og kanskje gå konkurs?

Du har lite empati med dei som verkeleg treng å drikke, kan det verke som....Ved juletider sto det vakter som sørget for at antall kunder i butikken ikke oversteg X. Funket greit det. Må vel kunne kjøre samme opplegget nå?Access Restricted

www.telegraph.co.uk

had to turn off the television news half a dozen times last week which, for a journalist who is obliged to stay on top of events, is quite something. I took this uncharacteristic step because I could not bear to watch, over and over again, the same film reports of appalling distress from hospital intensive care wards, some of them featuring interviews with patients who died after being filmed.

Presumably, the managers of broadcast news believe that this intrusive, emotionally manipulative programming is serving the national interest. By displaying the reality of the Covid epidemic and its consequences for the NHS, they are convincing those who doubt the seriousness of the situation – or who treat lockdown restrictions with contempt – that they are being criminally irresponsible.

I am sorry to have to tell all of you who are doing this in good conscience – the producers and the film crews, touring hospitals to make sensational film packages from the front line, perhaps with the encouragement of Government ministers – that the delinquents who organise illegal raves and the indifferent who host big parties ARE NOT WATCHING. They detached themselves long ago from this phenomenon which, for various reasons, they feel has nothing to do with them.

The people who are watching, sometimes obsessively, are the isolated, the lonely, and the already-frightened who are being driven further into the depths of terror and despair. In fact, I have spoken to a great many decent, rational, rule-following people who have switched off the television news coverage altogether because they find it too demoralising or voyeuristic.

Of course, it is right to report the genuine state of crisis in the hospitals and to include some testimony from their exhausted staff. But by the end of last week, the main news bulletins were being led, not by information and badly needed factual evidence, but by these highly personal stories which, in journalistic terms, should be considered feature “colour” pieces rather than news. And the 24-hour news channels were repeating the most upsetting of them, even if they were several days old, every hour of the day and night.

I can’t recall any national phenomenon – not even a wave of terror attacks – which has been treated with such relentless, repeated exposure of private suffering. The broadcasters will, of course, say that this is all being done with the consent of patients’ families. But bereaved or terrified relatives are not necessarily in a fit state to make judgments about what should be exposed, constantly, to the public gaze. That is a matter of principle for those who are responsible for these decisions.

They must ask themselves, what is the likely effect of this on those who are not switching off? It can only be a sense of utter helplessness and vicarious grief. Eventually this must result either in resignation – a state of clinical depression – or in anger. (Because people eventually resent being frightened.) Neither of these things are helpful in the present situation. Both, in fact, are destructive of public morale which might, in the end, produce less compliance, and can, in themselves, result in further collateral damage to mental health and to family relationships.

If the Government, or the NHS, is facilitating this campaign, it would seem to be yet another consequence of their failure to read the effect on the national consciousness of their own bizarre changes of tone. What happens to the public mood when they switch the optimism tap on and off with what seems, to an exasperated populace, like arbitrary whimsy? One day, there is a triumphal announcement of the (genuinely) stupendous, world-beating vaccination programme motoring along according to plan. And the next, there is Matt Hancock telling a television interviewer that we are a “long, long, long” (he actually did repeat the word three times) way from being able to lift restrictions.

How is anybody supposed to know what to make of this? If your personal physician were to tell you at one visit that your treatment was going very successfully and that you were recovering well. And then at the next, a day later, that it would be a “long, long, long” time before you could expect to lead anything like a normal life, you would probably conclude that he was incompetent – or a sadist.

Vi har et slikt orakel i NRK også. Husker ikke navnet, men det er som å høre Høie og Nakstad.Access Restricted

www.telegraph.co.uk

Hehe, jeg kan forstå at alkoholikere kan bli skikkelig syke av å ikke få noe. Men kan de ikke drikke øl sålenge da, jeg skjønner at det kanskje er kjipt, men alle må jo bidra noe, det er jo en dugnad dette eller var det ikke sånnDu har lite empati med dei som verkeleg treng å drikke, kan det verke som....

How the pandemic is affecting our children – by age

Try as we might, online learning can't match being in the classroom. We ask the education experts which children are falling furthest behindwww.telegraph.co.uk

Det er vel ganske opplagt at det er barn og unge som betaler den høyeste prisen for alt dette (samt de andre svakeste i samfunnet som feks de som har psykiske problemer, er arbeidsledige etc). Det er veldig vanskelig for meg å se at det kan være verdt det dessverre.Hun er blant «koronavinnerne»: – Jeg tilhører mindretallet. Jeg gruer meg nemlig litt til pandemien er over.

Psykolog Ragnhild Bang Nes har trygt hjemmekontor, fast lønn og rolige morgener. Forfatterne Liv Køltzow og Sandra Lillebø er andre som kommer godt ut av situasjonen.www.aftenposten.no

Mens her her vi noen andre som representerer de som danner meningene i samfunnet, veldig ressurssterke grupper, som faktisk gruer seg til dette over, for da må de dra på jobb om morgenen igjen, mine damer og herrer: kårånavinnerne

Med fare for å svare på et humorinnlegg.Hehe, jeg kan forstå at alkoholikere kan bli skikkelig syke av å ikke få noe. Men kan de ikke drikke øl sålenge da, jeg skjønner at det kanskje er kjipt, men alle må jo bidra noe, det er jo en dugnad dette eller var det ikke sånn

Øl duger liksom ikke.

helflaske vodka. 40 % * 0,7 l = 4,7 % * x

x= 6 liter.

12 halvlitere øl for en helflaske vodka. En alkoholiker har fort et mye høyere forbruk enn 1 helflaske i døgnet.

Var noen på nettet som kom med et eksempel der hvis denne alkoholikeren gikk under 2,5 (eller var det 2,0?) i promille så fikk alkoholikeren livsfarlig abstinens.Sist redigert:

Denne psykologen kan iallfall være fornøyd, litt til med kårånatiltak og kundegrunnlaget hennes kommer til å mangedobles. Hun kommer aldri til å bli arbeidsledigHun er blant «koronavinnerne»: – Jeg tilhører mindretallet. Jeg gruer meg nemlig litt til pandemien er over.

Psykolog Ragnhild Bang Nes har trygt hjemmekontor, fast lønn og rolige morgener. Forfatterne Liv Køltzow og Sandra Lillebø er andre som kommer godt ut av situasjonen.www.aftenposten.no

Mens her her vi noen andre som representerer de som danner meningene i samfunnet, veldig ressurssterke grupper, som faktisk gruer seg til dette over, for da må de dra på jobb om morgenen igjen, mine damer og herrer: kårånavinnerneFlere følger av den ene,geniale "planen" til regjeringen;

NAV-sjefen: – Titusener kan bli permittert

En rekke bedrifter har allerede permittert mange ansatte etter nedstengningen på Østlandet. NAV-direktøren tror omfanget kan bli større enn i november, da Oslo og flere andre kommuner strammet inn sist.e24.no

Slik går det, når de kun har brukt nasjonale tiltak, overser importsmitte og er totalt evneløse. Helt unødvendige permiterte og arbeidsledige, psykisk syke, folk som nektes aktiviteter i områder med lite smitte.

Jeg gir fullstendig blaffen i at noen prøver å forsvare det med "de andre hadde ikke gjort det bedre". Den elendige håndteringen står som en påle på egne ben- en påle av elendige valg, null planlegging, arroganse og snikk snakk.

De som frekventerer nevnte etablissement har fått med seg at det er en seriøs bedrift, vekter ved inngangen som holder orden på kundene. Ingen handlekurver, flaskene rett i posen. Fungerer bra. At man ikke oppfatter logikken forklarer mange av innleggene her synes jeg.Bare et fattig forsøk fra min side på å finne en logisk tråd i det som skjer for tidenHvorfor er det tryggere for kåråna inne på polet i forhold til i andre butikker

Hvorfor kan polet være oppe når feks andre små enkeltstående butikker med lite å gå på økonomisk må stenge og kanskje gå konkurs?

Flere følger av den ene,geniale "planen" til regjeringen;

NAV-sjefen: – Titusener kan bli permittert

En rekke bedrifter har allerede permittert mange ansatte etter nedstengningen på Østlandet. NAV-direktøren tror omfanget kan bli større enn i november, da Oslo og flere andre kommuner strammet inn sist.e24.no

Slik går det, når de kun har brukt nasjonale tiltak, overser importsmitte og er totalt evneløse. Helt unødvendige permiterte og arbeidsledige, psykisk syke, folk som nektes aktiviteter i områder med lite smitte.

Jeg gir fullstendig blaffen i at noen prøver å forsvare det med "de andre hadde ikke gjort det bedre". Den elendige håndteringen står som en påle på egne ben- en påle av elendige valg, null planlegging, arroganse og snikk snakk.Solberg: – Mange arbeidsplasser hadde gått tapt ved stengte grenser

Statsminister Erna Solberg (H) sier frykt for importsmitte må veies opp mot andre hensyn.e24.no

Husk denne. Mange arbeidsplasser ville gått tapt ved stengte grenser sa hun. (ikke at vi noen gang har manet om helt stengte grenser, bare 100 % kontroll på den)

Nå går arbeidsplasser tapt grunnet ikke-stengte grenser.

Statsministeren vår er statsministeren for polske, litauske og rumenske arbeidstakere. Norske arbeidstakere gir hun blanke i.Vår statsminister er konservativ. Det innebærer at hun ikke fungerer dersom hun må legge mer enn én plan. Ingen evne til å se ting komme, ingen alternative planer. Det henvises til tallene, eller de manglende tallene. Én plan, som tviholdes på. Med uovertruffen arroganse. Har da hatt med mange nok konservative å gjøre, til at jeg har vært borti den syken før.- Ble medlem

- 24.08.2018

- Innlegg

- 4.822

- Antall liker

- 3.163

Oppi all jamringa så er det ikke så mange eksempler å hente frem at så veldig mange andre land har håndtert det så mye bedre. Summa summarum har det gått ganske greit til nå, i et litt større perspektiv.

Danskene har en sosialdemokrat på toppen, der er det også lockdowns over en lav sko, mye mer enn her, i tillegg til at tallene på smittede og døde er mye mye værre.

Men for all del, forklaringen på at det har gått greit så langt kan gjerne være konservativ, det er ett fett for meg.Summa sumarium så stinker håndteringen til regjeringen. Grunnet manglende planlegging og alternative planer, har de nasjonale tiltak som eneste virkemiddel. Så pøser de på med lockdown for østlandet i tillegg.

Elendig.- Ble medlem

- 24.08.2018

- Innlegg

- 4.822

- Antall liker

- 3.163

Trodde du ville ha differensierte tiltak, eller vil du ha lockdown i hele landet?

Misforstår du med vilje?Trodde du ville ha differensierte tiltak, eller vil du ha lockdown i hele landet?

Selvsagt er jeg for differensierte tiltak. Og det er hverken lockdown eller nasjonale tiltak.jeg tror du bare må oppgi å få gjennomslag for noe som helst overfor folk som oppfører seg som om de er læringsresistent.- Ble medlem

- 24.08.2018

- Innlegg

- 4.822

- Antall liker

- 3.163

Er ikke så viktig for meg å få gjennomslag egentlig og har heller ingen forventninger, men det hadde jo vært kjedelig hvis det ikke var noen motstemmer? Kan jo ikke la dere svartmale i fredhere it comes

President Joe Biden har gjeninnført innreiserestriksjoner for nesten alle ikke-amerikanske borgere fra til sammen 30 land, deriblant Norge.

Innreiseforbudet gjelder for personer som har vært i Brasil, Sør-Afrika, Norge og 27 andre europeiske land i løpet av de to siste ukene før innreise til USA.

USA innfører innreiseforbud for personer fra 30 land – deriblant Norge

www.aftenposten.no

det synes å avtegne seg to mulige strategier, ser vi bort fra vaksinen:

enten stenger en grensene for korona, og slår ned (aka utrydder etter beste evne) viruset i landet for deretter å åpne opp (aka nz) (nye tilfeller lar seg bekjempe med sporing osv)

eller så lar en grensene være porøse, slik at vi danser mellom nedstengning og lettelse i en evig runddans. (og hvor sporing ikke greier å holde oss utenfor dansen.)

så langt har siste alternativ ikke vært helt heldig. det aner meg at det første får mer og mer gjennomslag.

så spørs det om vaksine blir gamechanger. med dagens tempo er ikke det rett rundt hjørnet.- Ble medlem

- 24.08.2018

- Innlegg

- 4.822

- Antall liker

- 3.163

Det meste tyder vel på at vaksinen blir en game changer, det som er noe dritt at det blir betydelig færre Astra vaksiner enn først antatt. Det var med den man skulle startet massevaksineringen på alvor- Ble medlem

- 24.08.2018

- Innlegg

- 4.822

- Antall liker

- 3.163

For de som irriterer seg over at alle tiltakene kommer i panikk og er dårlig funderte og ikke planlagt, kan man jo lese i veilederen fra fhi her, som det meste er basert på

erna, derimot, hun har en tredje mulighet (holder vi vaksine utenfor)– siden hun ikke ser alternativ 1:here it comes

President Joe Biden har gjeninnført innreiserestriksjoner for nesten alle ikke-amerikanske borgere fra til sammen 30 land, deriblant Norge.

Innreiseforbudet gjelder for personer som har vært i Brasil, Sør-Afrika, Norge og 27 andre europeiske land i løpet av de to siste ukene før innreise til USA.

USA innfører innreiseforbud for personer fra 30 land – deriblant Norge

www.aftenposten.no

det synes å avtegne seg to mulige strategier, ser vi bort fra vaksinen:

1) enten stenger en grensene for korona, og slår ned (aka utrydder etter beste evne) viruset i landet for deretter å åpne opp (aka nz) (nye tilfeller lar seg bekjempe med sporing osv

2) eller så lar en grensene være porøse, slik at vi danser mellom nedstengning og lettelse i en evig runddans. (og hvor sporing ikke greier å holde oss utenfor dansen.)

så langt har siste alternativ ikke vært helt heldig. det aner meg at det første får mer og mer gjennomslag.

så spørs det om vaksine blir gamechanger. med dagens tempo er ikke det rett rundt hjørnet.

«– Det mest positive scenariet er at vi får fullvaksinert den voksne befolkningen til juni, gradvis trapper ned tiltakene og åpner opp igjen.

– Worst case er at vi faktisk har de verste rundene foran oss. Det er i det perspektivet vi utreder portforbud. For vi må vite om det er nødvendig.»

Erna Solberg: – Vi kan ha det verste foran oss

Statsministeren er bekymret for smittesituasjonen etter utbruddet med mutert virus i Nordre Follo. – Worst case er at vi faktisk har de verste rundene foran oss, sier hun.www.aftenposten.no

Hvis ikke opposisjonen får henne under kontroll så blir det stygt. Det er viktig at FrP har kort lenke på henne nå.erna, derimot, hun har en tredje mulighet (holder vi vaksine utenfor)– siden hun ikke ser alternativ 1:

«– Det mest positive scenariet er at vi får fullvaksinert den voksne befolkningen til juni, gradvis trapper ned tiltakene og åpner opp igjen.

– Worst case er at vi faktisk har de verste rundene foran oss. Det er i det perspektivet vi utreder portforbud. For vi må vite om det er nødvendig.»

Erna Solberg: – Vi kan ha det verste foran oss

Statsministeren er bekymret for smittesituasjonen etter utbruddet med mutert virus i Nordre Follo. – Worst case er at vi faktisk har de verste rundene foran oss, sier hun.www.aftenposten.no

Sist redigert:- Ble medlem

- 24.08.2018

- Innlegg

- 4.822

- Antall liker

- 3.163

Syns du grensene er porøse nå? Er ikke så oppdatert på de siste reglene, men nå er det vel slik du har etterlyst?

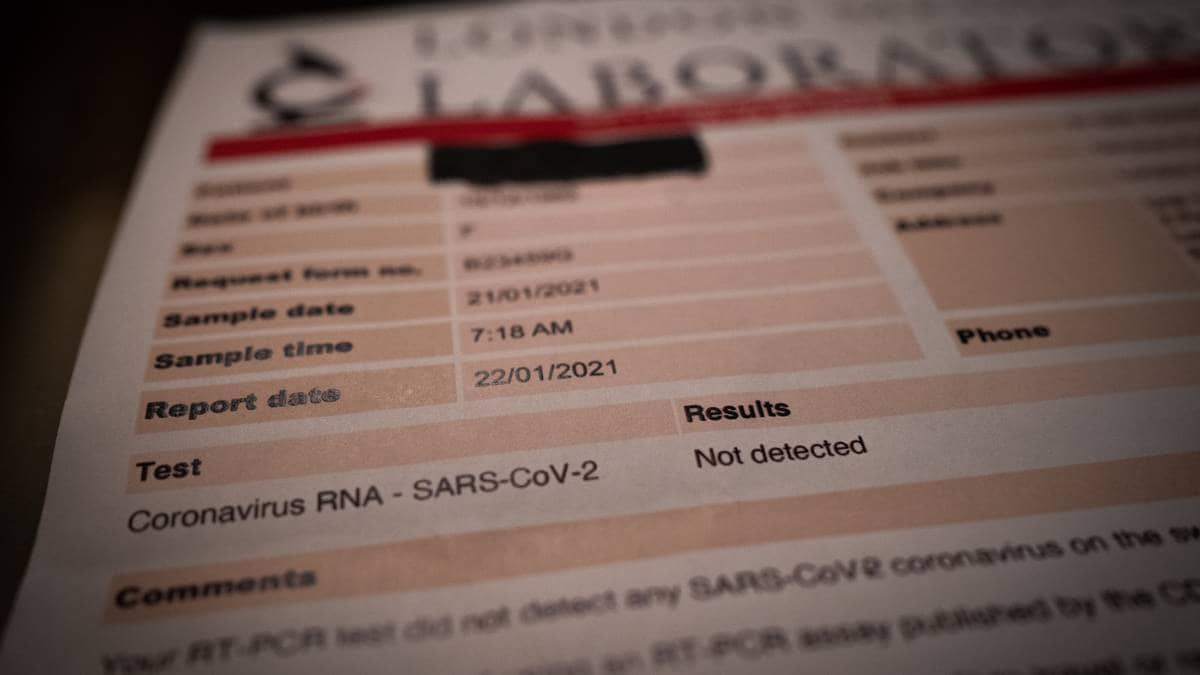

Så lett er det å få tak i en falsk polsk koronatest

Det tok NRK to timer og kostet 350 kroner å få tak i en negativ koronatest du kan bruke for å komme inn i Norge. Testen måtte betales i bitcoin i Polen. - Vi er klar over problemet, sier assisterende helsedirektør Espen Rostrup Nakstad. www.nrk.no

www.nrk.no

Husker vi hvor furtne Høyre var på opposisjonen forrige uke, fordi noen våget å åpne opp for vin til maten i indre troms. På fredag tvang regjeringen Bergen til lempe på importsmittekrav mot at arbeidsinnvandrere kunne vise til riktig dokument.

Artikkelen over viser at det tok nrk 2 timer å få tak i falsk negativ koronatest, mot en sum på 350 kroner. En ekte prøve koster deg 1000 kr.

Mon tro hvor enkelt det er å få et falskt dokument som dokumenterer tidligere smitte?

Kan vi få noen litt mindre naive til å styre oss? Noen som bryr seg om VÅR frihet og ikke bare friheten til polakker som skal inn i Norge.

på langt nær.Syns du grensene er porøse nå? Er ikke så oppdatert på de siste reglene, men nå er det vel slik du har etterlyst? -

Laster inn…

Diskusjonstråd Se tråd i gallerivisning

-

-

Laster inn…