Er det slik er det jo bare trist. Poenget må jo være å redde de små og mellomstore bedrifteneBunnfradrag i revers:

https://www.aftenposten.no/meninger...nen-slaar-haanden-av-de-smaa-georg-blichfeldt

Se på dette regnestykket: Bedriften Jørgen Hattemaker har 16.000 kroner i faste utgifter i april. Med 100 prosents inntektsbortfall vil staten gi ham 80 prosent i kompensasjon.

Men, nei. Før prosentregningen starter, fjerner staten 10.000 kroner. Da skal Jørgen ha 4800 kroner. Men, nei igjen. Det betales ikke ut beløp mindre enn 5000. Med andre ord: 100 prosent inntektsbortfall og null fra staten.

Bedriften Kong Salomo har også inntektsbortfall. Han har 25 millioner i faste utgifter. Når staten trekker fra 10.000 kroner før utregningen begynner, betyr det at han får dekket 80 prosent av 24.990.000 kroner

Politikk, religion og samfunn Finanskrisen

- Trådstarter BT

- Startdato

Diskusjonstråd Se tråd i gallerivisning

-

H

Hardingfele

Gjest

Det er slik. Konsekvensen er at dersom en virksomhet har lagt inn årene, permittert ansatte og slukket lyset, har de bedre utsikter til å få støtte enn virksomheter som har gjort et krafttak for å sikre omsetning og klare seg gjennom perioden.

Er det slik er det jo bare trist. Poenget må jo være å redde de små og mellomstore bedrifteneBunnfradrag i revers:

https://www.aftenposten.no/meninger...nen-slaar-haanden-av-de-smaa-georg-blichfeldt

Se på dette regnestykket: Bedriften Jørgen Hattemaker har 16.000 kroner i faste utgifter i april. Med 100 prosents inntektsbortfall vil staten gi ham 80 prosent i kompensasjon.

Men, nei. Før prosentregningen starter, fjerner staten 10.000 kroner. Da skal Jørgen ha 4800 kroner. Men, nei igjen. Det betales ikke ut beløp mindre enn 5000. Med andre ord: 100 prosent inntektsbortfall og null fra staten.

Bedriften Kong Salomo har også inntektsbortfall. Han har 25 millioner i faste utgifter. Når staten trekker fra 10.000 kroner før utregningen begynner, betyr det at han får dekket 80 prosent av 24.990.000 kroner

https://www.nrk.no/norge/krisehjelp...en-na-har-norge-sendt-alle-papirer-1.14984251GGjestemedlem

Gjest

Og det er jo bra og riktig. Dette er jo ikke ment å skulle være gratispenger til alle, men en støtte til de som ikke er i stand til å stå på egne ben. For de som klarer seg uten hjelp bør heller ikke hjelp tilbys.Det er slik. Konsekvensen er at dersom en virksomhet har lagt inn årene, permittert ansatte og slukket lyset, har de bedre utsikter til å få støtte enn virksomheter som har gjort et krafttak for å sikre omsetning og klare seg gjennom perioden.

https://www.nrk.no/norge/krisehjelp...en-na-har-norge-sendt-alle-papirer-1.14984251

Nå kan man sikkert tute om at det er "urettferdig" og at det kan føre til apati slik at man neste gang lar være å ty til egeninnsats. Men siden denne utbetalingen her nok er et engangstilfelle, eller i alle fall noe staten tyr til ytterst sjelden så har det i praksis ingen betydning.Mr Abe i Japan gir 10.000 til alle innbyggere i landet i form av helikopterpenger.

Typisk...jeg bor i et av de få landene i verden hvor staten har syltet på sparebøssa og ikke må utstede nye gjeldspapirer for å få råd til dette, men jeg får ikke kontantpengerJa syltet på sparebøssa betalt av felleskapet, ingen grunn til att enkelte mener de av den grunn kan parkere sugerøret i sprekken

De fleste av oss får ikke en dritt og må leve med det, de kaller det en dugnad for alle- Ble medlem

- 19.09.2014

- Innlegg

- 23.428

- Antall liker

- 16.318

Permitteringsreglene i Norge har kanskje ikke slått helt heldig ut... i Danmark har de brukt lønnskompensasjon for å holde folk i arbeid og i større grad beholde full lønn der staten tar mesteparten av regningen og arbeidsgiver en mindre del.

https://e24.no/norsk-oekonomi/i/kJr...har-ikke-tenkt-nok-paa-aa-holde-folk-i-arbeid- Ble medlem

- 19.09.2014

- Innlegg

- 23.428

- Antall liker

- 16.318

Noen som lurer på om det er i overkant mye olje i det amerikanske markedet om dagen? As we speak handles WTI, den amerikanske oljekontrakten med levering i mai på -6.70 dollar pr/ fat. Ja - oljeprisen i USA er nå negativ. Det er riktig nok en del spesielle forhold knyttet til denne kontrakten nå, Junikontrakten handles rundt 21 dollar til sammenligning.

Det som omtales som "oljeprisen" er strengt tatt prisen på den første futures-kontrakten da faktisk pris for fysisk olje avhenger av hvilken kvalitet man skal ha levert hvor og det finnes ganske mange ulike typer råolje, så det er normalt å forholde seg til futures-prisen. For noen dager siden vakte det en viss oppsikt da den amerikanske råvarebørsen CME på spørsmål bekreftet at hadde klargjort for negative priser på ymse kontrakter. Kan se ut som de kan få bruk for det nå.

"Vår" oljepris, altså brent, ligger på ca 26 dollar fatet med levering i mai.Det er en del som ikke forstår seg på oljemarkedet i USA ja. De har ikke noe sted å gjøre av den lette oljen da de fleste raffineriene er satt opp for tyngre olje. Canadierne sliter også og noen må betale for å bli kvitt oljen.. De som har satset på spot markedet og ikke lange kontrakter sliter nå. Det må nok stenges brønner i hele verden tenker jeg også her vil jeg tro.de blir vel baila ut der borte i bananland.

Bailouts satt jo langt inne under siste finanskrise i 2008-11. Mange politikere der borte hadde tungt for å svelge dette, man trådte liksom over en hellig strek.de blir vel baila ut der borte i bananland.

Men er det ikke rart med syndige ting man har gjort én gang, hvor mye lettere det er å gjøre igjen?

Bailouts og etterhvert helikopterpenger blir nok langt på vei like vanlig som quantitative easing programmer, rett og slett fordi alternativet blir så mye verre.

Noen av oss hevdet i klimatråden at vi kunne like gjerne la være å bygge ut i Vesterålen og Barentshavet fordi oljen ville være verdiløs før vi kom så langt som å ta den opp. Nå er dette spesielle omstendigheter i markedet som fører til negative priser, men det virker ikke usannsynlig med redusert etterspørsel i ganske lang tid fremover.Det er en del som ikke forstår seg på oljemarkedet i USA ja. De har ikke noe sted å gjøre av den lette oljen da de fleste raffineriene er satt opp for tyngre olje. Canadierne sliter også og noen må betale for å bli kvitt oljen.. De som har satset på spot markedet og ikke lange kontrakter sliter nå. Det må nok stenges brønner i hele verden tenker jeg også her vil jeg tro.HHardingfele

Gjest

Etterspørselen kan nok svinge seg opp igjen, men kostnadene for utvinning av olje i Arktis vil gi få om noen marginer, i en verden som både er i gang med en energitransformasjon og som begynner å innse at olje og gass koker kloden.

Krisemaksimeringsministeriet melder at i henhold til forskning, som bygger på det ubrytelige forholdet mellom CO2 skapt ved forbrenning av olje og gass og økning av CO2 i atmosfæren, kan vi ikke bruke mer enn 20% av kjente reserver fossilt dersom vi ønsker å unngå farlig global oppvarming.

Dette er et kjedelig faktum som gjør at man ivrer etter å angripe forskningen fremfor å gjøre noe med problemet.

Å satse på at Norge skal produsere olje og gass frem til 2070 er som å bygge store salmakerfabrikker i 1910, for produksjon frem til 2060.

IMF regner vel med å ta inn "det tapte" neste år, etter prognosene jeg har sett. Så oljeprisen blir ikke liggende i bunnpannen for godt.

Dette kan, selvsagt, være bra for konsumenter og næringsliv som skal hente seg inn igjen, om ikke for produsenter som er stuck i svart energi.Sist redigert av en moderator:

Å spå hvilken vei fremtiden vil ta i disse dager, er jammen ikke lett.Etterspørselen kan nok svinge seg opp igjen, men kostnadene for utvinning av olje i Arktis vil gi få om noen marginer, i en verden som både er i gang med en energitransformasjon og som begynner å innse at olje og gass koker kloden.

Krisemaksimeringsministeriet melder at i henhold til forskning, som bygger på det ubrytelige forholdet mellom CO2 skapt ved forbrenning av olje og gass og økning av CO2 i atmosfæren, kan vi ikke bruke mer enn 20% av kjente reserver fossilt dersom vi ønsker å unngå farlig global oppvarming.

Dette er et kjedelig faktum som gjør at man ivrer etter å angripe forskningen fremfor å gjøre noe med problemet.

Å satse på at Norge skal produsere olje og gass frem til 2070 er som å bygge store salmakerverksteder i 1910, for produksjon frem til 2060.

IMF regner vel med å ta inn "det tapte" neste år, etter prognosene jeg har sett. Så oljeprisen blir ikke liggende i bunnpannen for godt.

Dette kan, selvsagt, være bra for konsumenter og næringsliv som skal hente seg inn igjen, om ikke for produsenter som er stuck i svart energi.

Noen sier at olje og gass vil være så billig priset i mange år fremover at grønn energi vil bli priset ut av markedet. Andre sier at kriser som denne er akkurat det som skal til for å få fart på utviklingen av teknologi som vil fremskynde en grønn revolusjon.- Ble medlem

- 19.09.2014

- Innlegg

- 23.428

- Antall liker

- 16.318

-39.55 dollar var den på det laveste. Nå er den oppe i -17.

Som sagt har dette fint lite med prisen på fysisk olje å gjøre, men det er en artig kuriositet. Har aldri skjedd før.

For øvrig har det vært negative priser i strømmarkedet i Norge i det siste også. Og det er på ordentlig strøm, ikke derivatstrøm. Har forsåvidt skjedd før.

Du skal se att vi kommer til og leve godt på resursene våre i 50 år til minst , markedet er globalt og etterspørselen stopper ikke på sikt selv om vi er satt på vent en liten tid nåEtterspørselen kan nok svinge seg opp igjen, men kostnadene for utvinning av olje i Arktis vil gi få om noen marginer, i en verden som både er i gang med en energitransformasjon og som begynner å innse at olje og gass koker kloden.

Krisemaksimeringsministeriet melder at i henhold til forskning, som bygger på det ubrytelige forholdet mellom CO2 skapt ved forbrenning av olje og gass og økning av CO2 i atmosfæren, kan vi ikke bruke mer enn 20% av kjente reserver fossilt dersom vi ønsker å unngå farlig global oppvarming.

Dette er et kjedelig faktum som gjør at man ivrer etter å angripe forskningen fremfor å gjøre noe med problemet.

Å satse på at Norge skal produsere olje og gass frem til 2070 er som å bygge store salmakerfabrikker i 1910, for produksjon frem til 2060.

IMF regner vel med å ta inn "det tapte" neste år, etter prognosene jeg har sett. Så oljeprisen blir ikke liggende i bunnpannen for godt.

Dette kan, selvsagt, være bra for konsumenter og næringsliv som skal hente seg inn igjen, om ikke for produsenter som er stuck i svart energi.

Internationalt så vi en opptrapping innen exploration boring før covid, så dette faller på plass igjen ,velferdstaten kommer til og klare seg godt ,og takk for detHHardingfele

Gjest

Dersom oljen blir så billig priset i mange år fremover at grønn energi prises ut, betyr det at den oljen kommer fra steder der utvinningskost er på bunnivå. Og det bør man ta hensyn til når man planlegger hva Norge skal holde på med om 50 år.

Å spå hvilken vei fremtiden vil ta i disse dager, er jammen ikke lett.Etterspørselen kan nok svinge seg opp igjen, men kostnadene for utvinning av olje i Arktis vil gi få om noen marginer, i en verden som både er i gang med en energitransformasjon og som begynner å innse at olje og gass koker kloden.

Krisemaksimeringsministeriet melder at i henhold til forskning, som bygger på det ubrytelige forholdet mellom CO2 skapt ved forbrenning av olje og gass og økning av CO2 i atmosfæren, kan vi ikke bruke mer enn 20% av kjente reserver fossilt dersom vi ønsker å unngå farlig global oppvarming.

Dette er et kjedelig faktum som gjør at man ivrer etter å angripe forskningen fremfor å gjøre noe med problemet.

Å satse på at Norge skal produsere olje og gass frem til 2070 er som å bygge store salmakerverksteder i 1910, for produksjon frem til 2060.

IMF regner vel med å ta inn "det tapte" neste år, etter prognosene jeg har sett. Så oljeprisen blir ikke liggende i bunnpannen for godt.

Dette kan, selvsagt, være bra for konsumenter og næringsliv som skal hente seg inn igjen, om ikke for produsenter som er stuck i svart energi.

Noen sier at olje og gass vil være så billig priset i mange år fremover at grønn energi vil bli priset ut av markedet. Andre sier at kriser som denne er akkurat det som skal til for å få fart på utviklingen av teknologi som vil fremskynde en grønn revolusjon.

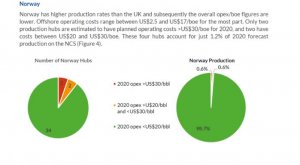

Det er jo et poeng at priskollapsen i stor grad ser ut til å skyldes en bevisst strategi om å slå ut USAs skiferoljeprodusenter. Det er ikke veldig god stemning der borte nå. Da er det mye annet som blir med i dragsuget også, jfr kostnadsestimatene i tabellen. Det er ikke godt å si hva som blir den nye likevektstilstanden etter corona, priskrig og konkurser, men det haster åpenbart ikke å åpne for mer leteboring i høykostregioner. Jeg ville heller ikke investert mye penger i underleverandører til åljå nå. Dette kan ta tid.Dersom oljen blir så billig priset i mange år fremover at grønn energi prises ut, betyr det at den oljen kommer fra steder der utvinningskost er på bunnivå. Og det bør man ta hensyn til når man planlegger hva Norge skal holde på med om 50 år.

Det blir ikke mye boring i nord nordpå nå nei. Det har det aldri heller vært. Selskap jeg jobber i og mange andre har som strategi som ikke inkluderer leting i Barenshavet. Normalt har mindre enn 10% av letebrønnene blir boret der.

Det er jo et poeng at priskollapsen i stor grad ser ut til å skyldes en bevisst strategi om å slå ut USAs skiferoljeprodusenter. Det er ikke veldig god stemning der borte nå. Da er det mye annet som blir med i dragsuget også, jfr kostnadsestimatene i tabellen. Det er ikke godt å si hva som blir den nye likevektstilstanden etter corona, priskrig og konkurser, men det haster åpenbart ikke å åpne for mer leteboring i høykostregioner. Jeg ville heller ikke investert mye penger i underleverandører til åljå nå. Dette kan ta tid.Dersom oljen blir så billig priset i mange år fremover at grønn energi prises ut, betyr det at den oljen kommer fra steder der utvinningskost er på bunnivå. Og det bør man ta hensyn til når man planlegger hva Norge skal holde på med om 50 år.

Oversikt kostander NCS

G

GGjestemedlem

Gjest

Mye vi kan leve av i fremtiden. F.eks. biodynamisk agurkolje og resirkulerte hamsterpellets. Men... så var det disse fornekterne da, hva skal vi gjøre med dem.- Ble medlem

- 19.09.2014

- Innlegg

- 23.428

- Antall liker

- 16.318

Det var i går og i dag er i dag og nå handles Juni-kontrakten (som nå effektivt er "oljeprisen" siden maikontrakten forfaller i dag) på litt over 15 dollar. Juli-kontrakten ligger litt under 21 dollar, begge de to sistnevnte er ned ca 5.5 dollar i dag, eller hhv ca 30% for juni og ca 20% for juli. Ser man langt frem handler WTI med forfall i desember 2021 på litt over 33 dolllar. Dette er vel og merke WTI-priser, ikke brent-priser som er mest relevante for Norge. Brent desember 2021 ligger på ca 38 dollar.husk at det bare er for mai. prisene for juni og juli ligger på 20-tallet.

Det går unna i oljemarkedet om dagen. Nå er ingen av disse lange prisene noe fasit og de kan, unnskyld - vil nok bli noe helt annet når alt kommer til alt, det går fort begge veier i tider som dette, men at ting er reltivt dramatisk i oljemarkedet er det liten tvil om. Dette er et massivt negativt etterspørselssjokk så blir spørmsålet hvor lenge det vare og hvor stor etterspørselen (og produksjonen) er når ting kommer tilbake til en eller annen ny normal på ett eller annet tidspunkt.- Ble medlem

- 19.09.2014

- Innlegg

- 23.428

- Antall liker

- 16.318

- Ble medlem

- 19.09.2014

- Innlegg

- 23.428

- Antall liker

- 16.318

Og i formiddag var i formiddag- Nå ligger juni på 11 dollar / fatet og juli på 18 dollar.

Det var i går og i dag er i dag og nå handles Juni-kontrakten (som nå effektivt er "oljeprisen" siden maikontrakten forfaller i dag) på litt over 15 dollar. Juli-kontrakten ligger litt under 21 dollar, begge de to sistnevnte er ned ca 5.5 dollar i dag, eller hhv ca 30% for juni og ca 20% for juli. Ser man langt frem handler WTI med forfall i desember 2021 på litt over 33 dolllar. Dette er vel og merke WTI-priser, ikke brent-priser som er mest relevante for Norge. Brent desember 2021 ligger på ca 38 dollar.husk at det bare er for mai. prisene for juni og juli ligger på 20-tallet.

Så har man en frykt som er sterkere enn frykten for lav oljepris og det er frykten for å ikke få tak i bøyelaster i juni-juli. Det svir virkelig på pungen i forhold til lav oljepris.

Og i formiddag var i formiddag- Nå ligger juni på 11 dollar / fatet og juli på 18 dollar.

Det var i går og i dag er i dag og nå handles Juni-kontrakten (som nå effektivt er "oljeprisen" siden maikontrakten forfaller i dag) på litt over 15 dollar. Juli-kontrakten ligger litt under 21 dollar, begge de to sistnevnte er ned ca 5.5 dollar i dag, eller hhv ca 30% for juni og ca 20% for juli. Ser man langt frem handler WTI med forfall i desember 2021 på litt over 33 dolllar. Dette er vel og merke WTI-priser, ikke brent-priser som er mest relevante for Norge. Brent desember 2021 ligger på ca 38 dollar.husk at det bare er for mai. prisene for juni og juli ligger på 20-tallet.- Ble medlem

- 19.09.2014

- Innlegg

- 23.428

- Antall liker

- 16.318

Care to elaborate? (Jeg skjønner bare ikke helt hva du sikter til)Så har man en frykt som er sterkere enn frykten for lav oljepris og det er frykten for å ikke få tak i bøyelaster i juni-juli. Det svir virkelig på pungen i forhold til lav oljepris.

Får man ikke lagret mer olje på plattformen eller båt for å losse den så blir man nødt til å stenge ned plattformen. Så kan man jo se for seg kostnadene som følger enten man kjører stengt plattform på diesel med minimumsbemanning eller en avbemannet plattform i ubestemt tid, er ikke sikkert det er plug and play å komme tilbake.

Care to elaborate? (Jeg skjønner bare ikke helt hva du sikter til)Så har man en frykt som er sterkere enn frykten for lav oljepris og det er frykten for å ikke få tak i bøyelaster i juni-juli. Det svir virkelig på pungen i forhold til lav oljepris.- Ble medlem

- 19.09.2014

- Innlegg

- 23.428

- Antall liker

- 16.318

Noen kan lese denne setningen 100 ganger, deretter skrive den 100 ganger:

En gjenstridig misoppfatning i den økonomiske debatten vil ha det til at det offentlige lever av privat sektor

Om det fremstår som gresk så kommer forklaringen allerede i neste avsnitt

Den som tviler på det, kan prøve å erstatte helsevesenet og Finansdepartementet med aluminiumsproduksjon neste gang vi rammes av en pandemSist redigert:GGjestemedlem

Gjest

En hyllest til Kina? Pleide ikke du å advare mot dem da..

Hypnotisert inn i et sosialistisk fengsel?

mehh..Jeg tror den der kanskje handler om USA, ikke Kina....GGjestemedlem

Gjest

Be Like Bill Meme GeneratorJeg tror den der kanskje handler om USA, ikke Kina....

The Fastest Meme Generator on the Planet. Easily add text to images or memes.

https://imgflip.com/memegenerator/Be-Like-Bill

..

I like the 2. don't blame me...

Du har nok rett.Jeg tror den der kanskje handler om USA, ikke Kina....The Fed Punishes Prudence

Its bailout for risky debt helps investors, not employees.

By Sam Long and Alexander Synkov

A deserted street in Washington, March 23.

PHOTO: MANDEL NGAN/AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE/GETTY IMAGES

The Federal Reserve’s recent decision to purchase trillions in corporate debt went underreported on Main Street, but shocked credit markets. The move will cushion losses for investors in risky assets, yet it’s a dubious step for American capitalism as a whole—one that will accelerate some of the most dangerous trends in the U.S. economy.

Altogether the Fed will deploy more than $1.45 trillion in support of investors in leveraged assets—more than double the size of the 2008 Troubled Asset Relief Program, and over $7,000 for each working-age American. That includes $750 billion to purchase recently downgraded junk bonds and bond exchange-traded funds—an unprecedented intervention in the private credit markets.

Pumping trillions of dollars into corporate credit and even high-yield debt will further distort markets already shaped by a decade of easy-money policies. This is no abstract concern. The result will be an acceleration of two economywide transfers of wealth: from the middle class to the affluent and from the cautious to the reckless.

The transfer from the middle class to the wealthy continues a trend begun in the wake of the 2007-09 financial crisis. Like the Fed’s combination of depressed interest rates and quantitative-easing government debt purchases, the new intervention will funnel trillions of dollars toward financial markets and the corporations able to participate in them.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell had little to say about the move, wrapping it in with the central bank’s broader mission to keep workers employed. But bankruptcies among highly leveraged businesses often pose surprisingly little risk to employment. More often than not, creditors choose to keep businesses staffed even when restructuring to retain value for the long-term. By preventing these bankruptcies, the Fed is doing more for equity holders and junior creditors than for employees.

Inflated asset prices spurred by years of low interest rates have also expanded the gap between investors and most Americans. The Fed’s purchases of high-yield ETFs and other instruments will widen it further. At the end of 2019, the average ratio of price to unleveraged cash earnings for S&P 500 companies was 13.4, more than a quarter higher than the 30-year average of 10.6. Drastic monetary stimulus may drive cyclically adjusted multiples even higher, pushing up returns for those who bet on risky assets relative to more cautious savers, many of whom have had meager earnings since the Fed cut interest rates 12 years ago. The average return on a five-year deposit, for example, dropped from 4% to 1% in the past decade.

Low interest rates are designed to encourage risk-taking. But the Fed’s pre-emptive bailout effectively eliminates risk retroactively. A CEO took a risk when he chose to borrow for share buybacks, as did an investor who bought a portfolio of highly leveraged loans. Making such risk-taking riskless necessarily makes prudence unprofitable in comparison. This is effectively a second transfer of wealth, from the most cautious participants in the economy to the most aggressive. At a time when millions of workers are being asked to sacrifice their incomes for the nation’s health, policy makers have chosen to punish savings and penalize prudence—a move that may undermine many Americans’ already wavering faith in capitalism.

Mr. Long is a search-fund investor in Boston. Mr. Synkov is a private-equity investor in New York.HHardingfele

Gjest

^Den som har videre tro på amerikansk kapitalisme er enten en "robber baron" eller en godtroende idiot. Siterer:

This is effectively a second transfer of wealth, from the most cautious participants in the economy to the most aggressive. At a time when millions of workers are being asked to sacrifice their incomes for the nation’s health, policy makers have chosen to punish savings and penalize prudence—a move that may undermine many Americans’ already wavering faith in capitalism.når vi nå er så godt igang!

In other words, the coronavirus has clarified that our government is weak, but the political reaction is to just accept the weakness of state institutions, and throw taxpayer money and political legitimacy at private institutions who govern in their stead.

[…]

There’s nothing wrong with mobilizing social resources in a crisis. But what is fascinating is that it is not the United States or EU governments doing so, but the United States of Asset Managers. They are the ones engaging in patent reform and structuring collaboration among industry competitors.

Along with public policymakers becoming sideline players is a new massive lobbying approach. The techlash is over, says the big tech booster brigade. The endless and cynical boosterism by big corporations was momentarily revealed by an Amazon memo unearthed by Vice, in which the corporation’s general counsel discussed “different and bold” ways to donate masks to maximize PR value, even as top executives were organizing a campaign to plant negative media stories about Amazon workers seeking protective equipment. “It’s a fantastic gift if we donate strategically,” he wrote.

[…]

So I’m seeing the early inklings of a turn away from the philosophy that got us into this mess. I hope we soon move beyond the empty moral grandstanding where Doritos commercials thank essential workers, which is just a variant of ‘support the troops’ as a guilt-ridden way of either not serving in combat or supporting knowingly immoral wars for which one pays no cost. We have to restructure our social hierarchy, so that people who do the work have control over the work, instead of the middlemen and monopolists.

To that end, putting forward a merger moratorium is a good first step. But we’re going to need much more. We will need a temporary Pandemic Antitrust Act to break apart companies that have gained power because of the pandemic. We do not want a world where, as Jim Cramer fears, there are just three retailers, Amazon, Walmart, and Costco. Such a bill could be modeled on Senator Phil Hart’s early 1970s legislation titled the “Industrial Reorganization Act,” which would have established a commission to break apart corporations with a certain market share threshold. It could be a no-fault monopolization statute, which means it wouldn’t be a law enforcement regime requiring proof of wrongdoing. It isn’t Bezos’s doing that he gained massive amounts of power during the pandemic, and it shouldn’t be seen as a penalty to restructure Amazon. It’s just break-up via policy, simply because we want people to be able to run businesses independent of a few giants. The goal is to save and expand opportunity in commerce for all of us.

artikkelen av stoller bør leses i sin helhet.

Antitrust After the Coronavirus

The pandemic has clarified a lot about America and the West. Now comes the political reaction.Sist redigert:

Vi er i en verden der oljeprisen har vært i fritt fall, norge punger ut minimum 500 milliarder ekstraordinært, nærmer oss 400 000 arbeidsløse, full stopp i forbruk, egentlig full stopp i hele samfunnet. Allikevel faller børsene tross alt bare bagatellmessig. Er det virkelig slik at markedet tror dette bare blåser over? Ser i dag at Norwegian ikke tror flytrafikken nærmer seg normale forhold før lang ut i 2022 og det skulle vel i så fall også bety at samfunnet heller ikke er normalt før den tid. -

Laster inn…

Diskusjonstråd Se tråd i gallerivisning

-

-

Laster inn…