Jeg forstår at det kan være vanskelig noen ganger. At du ønsker å bruke tid på en østens biskop og hans propaganda er jo opp til deg, ja.Når du først skriver at det ikke finnes noen link til mitrofaens uttalelser (dvs at du mener at det ikke er sant at han har sagt dette), får fremlagt en link til en kommentarartikkel om disse uttalelsene, og avfeier denne kommentaren som «propaganda», så gjør du det veldig vanskelig for andre å fatte dette, ja. Det ser mer ut som du padler.

Mulig du mener noe annet enn du skrev, men vi andre må forholde oss til hva du faktisk skriver. Vi er ikke tankelesere.

Jeg synes nok det er verdt å bruke litt tid på å diskutere at en muskovittisk biskop med bakgrunn som etterretningsoffiser erklærer Øst-Finnmark som «hellig ortodokst land», sier at grenseavtalen fra 1826 er illegitim, og vil opprette et pastorat i Kirkenes. Riktignok sier han også i sin storsinnethet at han ikke vil kreve landet «tilbake». Ennå.

Politikk, religion og samfunn Russland - En tikkende bombe eller bare fjas?

Diskusjonstråd Se tråd i gallerivisning

-

Han bruker vel først og fremst tid på tøvet ditt. Det er åpenbart bortkastet.

Ad verdien og sannhetsgehalten på innholdet i skriveriene så er vel KGB-patriarken og den herværende ganske likeverdige, så det blir jo litt sånn hipp som happ.Rysslands försvarsminister i Nordkorea för militära möten – Senaste nytt om kriget i Ukraina

Rysslands storskaliga invasion av Ukraina har pågått sedan den 24 februari 2022, då ryska trupper anföll Ukraina från flera håll. Ryssland ockuperar flera regioner i östra och södra Ukraina. Här hittar du SVT:s liverapportering om kriget. www.svt.se

www.svt.se

Kina: Redo att samarbeta om kabelbrott i Östersjön

Kina säger sig vara berett att samarbeta med de berörda länderna för att ta reda på vad som hände när två datakablar i Östersjön skadades. – Det är positivt om Kina vill samarbeta. Det är viktigt att bringa klarhet i det som skett. Vi har en pågående dialog, säger Sveriges utrikesminister Maria... www.svt.se

Som nevnt tidligere så tror jeg ikke dette var en kinesisk operasjon, og hvis Jinping synes det er greit at Putin bruker et kinesisk skip til sabotasjeaksjoner i Europa så har vi større utfordringer å hanskes med enn det vi (jeg) hittil har trodd.

www.svt.se

Som nevnt tidligere så tror jeg ikke dette var en kinesisk operasjon, og hvis Jinping synes det er greit at Putin bruker et kinesisk skip til sabotasjeaksjoner i Europa så har vi større utfordringer å hanskes med enn det vi (jeg) hittil har trodd.

Mer her i dag:WarTranslated (Dmitri) (@wartranslated.bsky.social)

Reuters writes that US intelligence believes that authorizing strikes by Western weapons deep into Russia has not increased the risk of nuclear escalation. Some U.S. officials now believe that concerns about escalation, including nuclear fears, have been exaggerated. bsky.app

bsky.app

No shit, Sherlock.

^^ Hypotesen er vel at Russland, kanskje i samforståing med Kina, har instruert den kinesiske båten om å dorga etter datakablar.

^^ Hypotesen er vel at Russland, kanskje i samforståing med Kina, har instruert den kinesiske båten om å dorga etter datakablar.

I så fall er det vel hendig om det offisielle kinesiske svaret er at «dette veit vi ingenting om, men de må gjerne gjera undersøkingar og avhøyra mannskapet». Kapteinen har i så fall tre val:

a) hevda at dette var eit hendeleg uhell. I så fall vert vel reiarlaget økonomisk ansvarleg, og kapteinen kan planleggja ei framtid som hjelpemannskap på djunke resten av yrkeslivet.

b) fortelja at han på eige initiativ tok på seg dette oppdraget frå Russland, og planleggja ei framtid i omskuleringsleir resten av livet.

c) fortelja at han, etter ordre frå høgste kinesiske hald, tok på seg oppdraget, og planleggja ei framtid som død.

Uansett er det eit godt teikn dersom Kina har tenkt å slutta å påta seg denne typen oppdrag fråKinaRussland.Sist redigert:Det aller meste av militærhjelpen som sendes til Ukraina, går gjennom Rzeszow-Jasionka-flyplassen. Nå skal NATO beskytte denne viktige flyplassen sør i Polen.

Norge skal beskytte flyplass i Polen

Norge har tatt på seg ansvar for å beskytte det viktigste knutepunktet for transport av militært utstyr til Ukraina.www.aftenposten.no

Stemmer det at den kinajolla stort sett har russisk mannskap??^Jeg er rimelig sikker på at Bejing ikke ønsker å delta i simpel sabotasje som dette. Putins krig er allerede en stor (nok) belastning for Kina.

Den kinesiske eksporten skjer hovedsaklig med båtfrakt. Trolig hundrevis av containerskip som anløper europeiske havner hver eneste dag.

Det ville være idioti av kinesiske skip å drive åpenlys sabotasje mot Europa. Man spytter ikke på tallerkenen man spiser av.

Tipper kinesiske myndigheter medvirker til full etterforskning og lar den antatt korrupte kapteinen få sin straff.- Ble medlem

- 27.03.2007

- Innlegg

- 21.521

- Antall liker

- 33.344

- Sted

- Nede i fjæresteinene

- Torget vurderinger

- 2

Har i hvert fall lest at kapteinen er russisk.Stemmer det at den kinajolla stort sett har russisk mannskap??

MvhIkke som jeg kjenner til. Har ikke sett noe annet enn at den har kinesisk mannskap, etter en første forveksling av havnelosen med kapteinen.

Det er også et viktig signal som bør sendes til putin om at Østersjøen nå er en NATO-innsjø. Sund og bælter er stengt for ham og oljetankerne hans hvis han ikke oppfører seg. Han forstår rå overmakt.^Jeg er rimelig sikker på at Bejing ikke ønsker å delta i simpel sabotasje som dette. Putins krig er allerede en stor (nok) belastning for Kina.

Den kinesiske eksporten skjer hovedsaklig med båtfrakt. Trolig hundrevis av containerskip som anløper europeiske havner hver eneste dag.

Det ville være idioti av kinesiske skip å drive åpenlys sabotasje mot Europa. Man spytter ikke på tallerkenen man spiser av.

Tipper kinesiske myndigheter medvirker til full etterforskning og lar den antatt korrupte kapteinen få sin straff.

Nei ikke helt, sjekk tidligere poster bla WSJ, der er det en uttalelse om at både denne og tidligere New Polar Bear har russisk mannskap ombord. Det sies vel ikke hvor mangeHar i hvert fall lest at kapteinen er russisk.

MvhSvalbard er som nevnt tidligere et potensielt område hvor artikkel 5 kan bli testet ut...

Nå nevnes Svalbard flere steder;

Tysk etterretningssjef nevner Svalbard som russisk mål

Russisk sabotasje og hybrid krigføring mot vestlige mål kan utløse Natos artikkel 5, advarer tysk etterretningssjef. www.nettavisen.no

www.nettavisen.no

Diesen: – Må være villige til å ofre titusenvis av arbeidsplasser

Europa har 172 ulike våpensystemer der USA har 32. Det nytter ikke hvis forsvarsevnen skal opp, mener tidligere forsvarssjef. www.nettavisen.no

Den russiske økonomien kollapser, mener ekspert - som viser til nye sjokkpriser på en rekke kjente matvarer.Angående yi peng 3. Noen som aner hva tyskerne vil der ute nå?Nettopp.... Sammen med en mindre danske. Som har nærmet seg i 25 knop

www.nettavisen.no

Den russiske økonomien kollapser, mener ekspert - som viser til nye sjokkpriser på en rekke kjente matvarer.Angående yi peng 3. Noen som aner hva tyskerne vil der ute nå?Nettopp.... Sammen med en mindre danske. Som har nærmet seg i 25 knop

Vaktskifte?

Nei, men det var enormt mye aktivitet i går, stille i dag formiddag. Nå ser det ut til at den tyske fregatten har passert på vei nordover og de to danske patruljebåtene er på vei sørover, mens det tyske kystvaktskipet og en dansk patruljebåt holder vakt ved kineseren. Jeg aner ikke hvor den fregatten skal, den har ikke oppgitt noen destinasjon i AIS.Angående yi peng 3. Noen som aner hva tyskerne vil der ute nå?Det ser ut som om F223 (den store tysker'n) snur og går sydover igjen. Han tok en liten S sving i lo for bad duben (den mindre tysker'n). En slik manøver ville jeg brukt for å plukke opp noe, eller noen, fra sjøen. Det ser ut for meg som om f223 fik noe ombord. Dette samtidig med dansk vaktskifte..... Herlig med ais. Kan lage helt egne konspirasjoner....

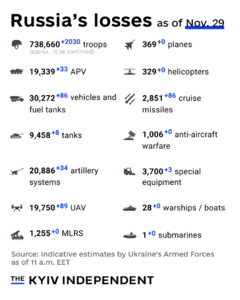

Rart, leste nettopp i VG denne uka at økonomien går så det griner følge offisielle tall, kommentert av en norsk forsker. Arbeidsledigheten er lav. Det kan jo ha en sammenheng med de 700 000 indisponerte.Den russiske økonomien kollapser, mener ekspert - som viser til nye sjokkpriser på en rekke kjente matvarer.

Her hjemme så ser dem ikke andre tall enn hva putte gir dem, og putte gir ut så mye vrøvl at enn skal miste oversikten....Rart, leste nettopp i VG denne uka at økonomien går så det griner følge offisielle tall, kommentert av en norsk forsker. Arbeidsledigheten er lav. Det kan jo ha en sammenheng med de 700 000 indisponerte.

MI6-sjefen: Russland driver ekstremt hensynsløs sabotasje i Europa

Russland fører en «ekstremt hensynsløs» saboteringskampanje i Europa, sier MI6-sjefen. Russiske sabotasjeaksjoner i Europa vil øke, ifølge amerikansk etterretning. www.finansavisen.no

www.finansavisen.no

Som om at et anker kan tilfeldigvis ha laget et hull i eget skip..... som igjen tilfeldigvis er kinesisk ?Kan man drive særdeles omtenksom sabotasje?

PloppZelenskyj öppnar för vapenvila – mot Natobeskydd – Senaste nytt om kriget i Ukraina

Rysslands storskaliga invasion av Ukraina har pågått sedan den 24 februari 2022, då ryska trupper anföll Ukraina från flera håll. Ryssland ockuperar flera regioner i östra och södra Ukraina. Här hittar du SVT:s liverapportering om kriget. www.svt.se

www.svt.se

Nato ökar närvaron över Östersjön – spanar med flygpatruller

Frankrike och Nato ökar sin närvaro över Östersjön – varje månad lyfter nu franska spaningsplan från Sverige för patrulluppdrag över havet. – Det är ett spänt läge, säger missionschefen Geoffrey. Följ med i ombord i videoreportaget. www.svt.se

www.svt.se

De bestemte seg i 2018 for å gå vekk fra Kyrilliske til latinske bokstaver innen 2025Up yours, putte.

Vis vedlegget 1078531

Kasakhisk farvel til kyrillisk. | Aftenposten Innsikt

www.aftenposteninnsikt.no

Men de og andre land må ta det langsomt (utsatt til 2031?), for ikke å provosere ruzzland

Kvitter seg med russisk alfabet

De tyrkisktalende landene er enige om ett offisielt alfabet. For noen land må overgangen fra det russiske alfabetet til det nye skje gradvis for å ikke provosere Russland.www.abcnyheter.no

Alle nabolandene skjønner at felles språk, valuta, (u)kultur osv., lett kan bli brukt av imperialistene i Moskva til å invadere eller på annen måte underkue dem.Krysser fingrene til neste satellittbilder

Eg har forstått det slik at kyrillisk og latinsk alfabet har litt ulike styrkar i ulike språk. No er det mogleg at eg rotar, men eg trur den første bølgja av skriftfesting under Sovjetunionen brukte ein del latinsk (også for ikkje-tyrkiske språk) og at det vart bytta til kyrillisk under Stalin i 1937.De bestemte seg i 2018 for å gå vekk fra Kyrilliske til latinske bokstaver innen 2025

Edit: Det er vagt OT, men den enorme alfabetiseringa av minoritetsspråk (også dei uralske og finsk-ugriske som @Asbjørn la fram kart over litt tidlegare), i ein periode då minoritetar vart assimilerte over ein låg sko i Vest (altså, i den tidlege fasen av Sovjetunionen), er eit ganske interessant fenomen.

Las også at Mao planla ein overgang frå hanzi etter revolusjonen, men at Stalin argumenterte kraftig mot: skulle dei alfabetisera, burde dei bruka eit nasjonalt alfabet, ikkje latinske bokstavar.

Fann ikkje att teksten, men står litt i denne Reddit-tråden:

https://www.reddit.com/r/todayilearned/comments/7wfo9u

Mao Zedong (who was Mao Tse-tung before pinyin, under the “Wade-Giles” romanisation system) wanted a radical break with old ways after 1949, when the civil war ended in mainland China. He was hardly the first to think that China’s beautiful, complicated and inefficient script was a hindrance to the country’s development. Lu Xun, a celebrated novelist, wrote in the early 20th century: “If we are to go on living, Chinese characters cannot.”

But according to Mr Zhou, speaking to the New Yorker in 2004, it was Josef Stalin in 1949 who talked Mao out of full-scale romanisation, saying that a proud China needed a truly national system. The regime instead simplified many Chinese characters, supposedly making them easier to learn.Sist redigert:Ukraina vill ansöka om Natomedlemskap – Senaste nytt om kriget i Ukraina

Rysslands storskaliga invasion av Ukraina har pågått sedan den 24 februari 2022, då ryska trupper anföll Ukraina från flera håll. Ryssland ockuperar flera regioner i östra och södra Ukraina. Här hittar du SVT:s liverapportering om kriget. www.svt.se

www.svt.se

-

Laster inn…

Diskusjonstråd Se tråd i gallerivisning

-

-

Laster inn…