Trump er jo enig med alle de han prater med på tomannshånd. Han blir jo 'overbevist' hver gang. Får håpe han snart prater et par minutter med en som har greie på feks. miljøvern, så blir han kanskje overbevist 'sånn plutselig' her også.

Politikk, religion og samfunn President Donald J. Trump - Quo vadis? (Del 1)

Diskusjonstråd Se tråd i gallerivisning

-

- Status

- Stengt for ytterligere svar.

^

Det tror jeg er helt feil. Hvorfor skulle han være det. Men han vil sikkert være enig i siste taler såfremt det er til hans fordel, på en eller annen måte. Det lager selvfølgelig ikke noen overordnet strategi og plan ut over hva han til enhver tid finner opportunt.

Vel, han forholdt seg ikke til Assad sin gassing i Syria før han ser bilder av barn på TV og snakker med Ivanka. Da var dette aldeles forferdelig og så rådfører han seg med Kushner før han reiser til Israel og da har han veldig klare oppfatninger om ting. På meg så virker det som om han vet hva som foregår ned til nærmeste lyskryss og utover dette er han fullstendig ignorant og slenger ut en haug med forutinntattheter helt til han blir eksponert for fakta som vekker følelser i ham. Han vingler også voldsomt fra det ene til det andre hver gang han holder møter med statsledere, feks. Kina, Sør Korea, mfl.^

Det tror jeg er helt feil. Hvorfor skulle han være det. Men han vil sikkert være enig i siste taler såfremt det er til hans fordel, på en eller annen måte. Det lager selvfølgelig ikke noen overordnet strategi og plan ut over hva han til enhver tid finner opportunt.Nå kutter Trump samarbeidet med Kina angående Nord Korea

Trump sier han gir opp Kina-samarbeid om Nord-Korea - Donald Trump - VG

USAs president Donald Trump går igjen hardt ut mot Kina og mener landet gjør lite for å stoppe Nord-Koreas rakettoppskytninger. Nå sier han opp samarbeidet via Twitter.

"Dagen etter at Nord-Korea ypper seg med enda en missiloppskytning angriper USAs president Donald Trump Kinas handelspolitikk.

I sin siste twittermelding virker det som at Trump gir opp samarbeidet med Kina om å stanse Nord-Koreas prøveoppskytninger.

– Handelen mellom Kina og Nord-Korea vokste nesten 40 prosent i første kvartal. Så mye for Kina som samarbeider med oss – men vi måtte gi det et forsøk!"- Ble medlem

- 05.02.2015

- Innlegg

- 2.954

- Antall liker

- 316

CNN i hardt vær igjen, litt Stasi stil over dette.

Trump hadde rett igjen:Venstreorienterte Vox.com sluttet seg til 4Chan, wikileaks, og Donald Trump jr. CNN brøt med ethos på nettet: Man truer ikke folk.

Da CNN forsto backlashet sendte de ut en melding der de benektet at de hadde presset HanAssholeSolo, men den opprinnelige meldingen lot seg ikke tilbakekalle.

CNN har ertet på seg «undergrunnen» på nettet og der forsvarer man ytringsfriheten på tvers av politisk tilhørighet.

Unfortunately for CNN, memes are like a hydra: when you cut off one head, many more grow in its place. And the Internet has now dedicated itself to ensuring that the network utterly fails in its mission to eradicate underground Internet culture.

https://www.document.no/2017/07/06/cnn-upopulaere-pa-trussel-om-outing/Trump har hele tiden sagt at CNN er ute etter å knuse ikke bare ham, men politisk opposisjon i Amerika. Nå har CNN gitt bevis for at han har rett.

Sett i lys av hvor ofte helten din juger, misoppfatter og forvrenger virkeligheten er det nok smart å telle disse tilfelleneTrump hadde rett igjen:HHardingfele

Gjest

Trump-velgere er mot Obamacare, som de ellers setter stor pris på, men misliker? Så nå kjemper klinikker i konservative deler av landet for å få velgerne til å forstå at den helsehjelpen de får kommer fra sosialistkommunistmuslimkenyaneren:

Conservative Corner Of California Pushes To Preserve Obamacare : Shots - Health News : NPR

One patient at the Mountain Valleys clinic in Bieber, Kay Roope, 64, knew she had Medi-Cal, and she liked it.

"It did me good," she says.

Now she has a subsidized commercial plan through Covered California with modest premiums and copays, and she likes that, too.

"It's OK, 'cause I'm at the doctor's at least once a month," she says.

But when asked what she thinks of Obamacare overall, she says she doesn't like it.

"Because of Obama himself," she says with a laugh. "I rest my case."

The confusion and the contradictions are common among patients, explains Morris, the enrollment counselor.

"People just don't understand the different names," she says. "But of course, it's the same thing."

Morris has seen the difference the Affordable Care Act has made for people in the region. She has seen patients get treatment for diabetes and breast cancer, or get knee surgery that they otherwise wouldn't have gotten.

Those patients won't fight for Obamacare, Morris says, so that's why the clinics have to.

Lettere å holde orden på små tall enn store, ja.

Sett i lys av hvor ofte helten din juger, misoppfatter og forvrenger virkeligheten er det nok smart å telle disse tilfelleneTrump hadde rett igjen:HHardingfele

Gjest

Mer tøys fra Fjernis. Trump la CNN for hat tidlig, pga et par kritiske reportasjer om ham. Han hengte dem ut, stengte dem ute fra pressekonferanser, nektet å ta spørsmål fra dem og kalte dem Fake News. For å skape en fiende som tilhengerne hans kunne fokusere på. Trump har sikkert hatt noe uoppgjort med Ted Turner, for alt man vet.

Sett i lys av hvor ofte helten din juger, misoppfatter og forvrenger virkeligheten er det nok smart å telle disse tilfelleneTrump hadde rett igjen:

Dermed ble CNN målskive. Hva skulle nyhetskanalen gjøre? Slutte å dekke nyhetene? Slutte å være kritiske der Trump fortjener kritikk? Målet med MSM-memet og kritikken mot "jøde-eide media" er å forsøke å kue disse, få dem til å holde kjeft eller få dem til å skygge unna å dekke saker slik at de skader Trump og hans regime.

Det aller viktigste som Den amerikanske revolusjonen ga verden var nettopp trykke- og ytringsfriheten. Merkelig nok har fjernis angrepet denne (1. grunnlovstillegg) og han innbiller seg sikkert at han gjør noe klokt når han plaprer med idolet sitt.- Ble medlem

- 05.02.2015

- Innlegg

- 2.954

- Antall liker

- 316

Tja, han juger ikke mer enn politikere flest, og for 4 gang, han er ikke min helt men jeg koser meg med å se den råtne media og de politiske korrekte dumme seg ut gang på gang.

Sett i lys av hvor ofte helten din juger, misoppfatter og forvrenger virkeligheten er det nok smart å telle disse tilfelleneTrump hadde rett igjen:Tøv. Mannen juger og tøver så det renner av han. Han stiller i ekstraordinær klasse - kun overgått av Kim og Bagdad Bob.

Sjekk fra Politifact:

Trump har 21% mostly false, 32% false og 16% "Pants on fire" - totalt 69% usannheter.

Paul Ryan til sammenligning har 28% Mostly false, 9 % false og 5 % "Pants on fire" - totalt 43% usannheter

Mitch McDonnel ligger likeledes på 43% usannheter.

Bernie Sanders til sammenligning ligger på 28% usannheter (hvorav ingen "Pants on fire").

(Det ser ut til at republikanerne som har en del saker, ligger på jevnt 40-45%. Jeg regner med at en god del her henger på Obamacare...)

Johan-KrSist redigert:

Noen ganger lurer jeg på om Fjernis lever på den samme planeten som meg...Tøv. Mannen juger og tøver så det renner av han. Han stiller i ekstraordinær klasse - kun overgått av Kim og Bagdad Bob.

Sjekk fra Politifact:

Trump har 21% mostly false, 32% false og 16% "Pants on fire" - totalt 69% usannheter.

Paul Ryan til sammenligning har 28% Mostly false, 9 % false og 5 % "Pants on fire" - totalt 43% usannheter

Mitch McDonnel ligger likeledes på 43% usannheter.

Bernie Sanders til sammenligning ligger på 28% usannheter (hvorav ingen "Pants on fire").

(Det ser ut til at republikanerne som har en del saker, ligger på jevnt 40-45%. Jeg regner med at en god del her henger på Obamacare...)

Johan-Kr- Ble medlem

- 05.02.2015

- Innlegg

- 2.954

- Antall liker

- 316

Da kan jeg jo bruke en av standard setningen deres, kilden er ikke troverdig.Tøv. Mannen juger og tøver så det renner av han. Han stiller i ekstraordinær klasse - kun overgått av Kim og Bagdad Bob.

Sjekk fra Politifact:

Trump har 21% mostly false, 32% false og 16% "Pants on fire" - totalt 69% usannheter.

Paul Ryan til sammenligning har 28% Mostly false, 9 % false og 5 % "Pants on fire" - totalt 43% usannheter

Mitch McDonnel ligger likeledes på 43% usannheter.

Bernie Sanders til sammenligning ligger på 28% usannheter (hvorav ingen "Pants on fire").

(Det ser ut til at republikanerne som har en del saker, ligger på jevnt 40-45%. Jeg regner med at en god del her henger på Obamacare...)

Johan-Kr

Occupy Democrats's file | PolitiFactOccupy Democrats, founded in 2012, is an advocacy group created to counterbalance the Republican tea party, and to "give President Obama and other progressive Democrats a Congress that will work with them to grow the economy, create jobs, promote fairness and fight inequality, and get money out of politics!"

Nå holder Trump lovnaden om Obamacare, dere kritiserer han for det også, er dere aldri fornøyd, må være vanskelig å være så misfornøyd at man må klage på et forum flere ganger om dagen over flere år på alt man ikke er enig i.- Ble medlem

- 05.02.2015

- Innlegg

- 2.954

- Antall liker

- 316

Kan du ikke bruke det andre nicket ditt, det du hadde før defacto.

Noen ganger lurer jeg på om Fjernis lever på den samme planeten som meg...Tøv. Mannen juger og tøver så det renner av han. Han stiller i ekstraordinær klasse - kun overgått av Kim og Bagdad Bob.

Sjekk fra Politifact:

Trump har 21% mostly false, 32% false og 16% "Pants on fire" - totalt 69% usannheter.

Paul Ryan til sammenligning har 28% Mostly false, 9 % false og 5 % "Pants on fire" - totalt 43% usannheter

Mitch McDonnel ligger likeledes på 43% usannheter.

Bernie Sanders til sammenligning ligger på 28% usannheter (hvorav ingen "Pants on fire").

(Det ser ut til at republikanerne som har en del saker, ligger på jevnt 40-45%. Jeg regner med at en god del her henger på Obamacare...)

Johan-Kr- Ble medlem

- 05.02.2015

- Innlegg

- 2.954

- Antall liker

- 316

Fake News, CNN angrep Trump fra første stund da de fant ut at han faktisk kunne vinne valget.

Mer tøys fra Fjernis. Trump la CNN for hat tidlig, pga et par kritiske reportasjer om ham. Han hengte dem ut, stengte dem ute fra pressekonferanser, nektet å ta spørsmål fra dem og kalte dem Fake News. For å skape en fiende som tilhengerne hans kunne fokusere på. Trump har sikkert hatt noe uoppgjort med Ted Turner, for alt man vet.

Sett i lys av hvor ofte helten din juger, misoppfatter og forvrenger virkeligheten er det nok smart å telle disse tilfelleneTrump hadde rett igjen:

Dermed ble CNN målskive. Hva skulle nyhetskanalen gjøre? Slutte å dekke nyhetene? Slutte å være kritiske der Trump fortjener kritikk? Målet med MSM-memet og kritikken mot "jøde-eide media" er å forsøke å kue disse, få dem til å holde kjeft eller få dem til å skygge unna å dekke saker slik at de skader Trump og hans regime.

Det aller viktigste som Den amerikanske revolusjonen ga verden var nettopp trykke- og ytringsfriheten. Merkelig nok har fjernis angrepet denne (1. grunnlovstillegg) og han innbiller seg sikkert at han gjør noe klokt når han plaprer med idolet sitt.HHardingfele

Gjest

En økonomiprisvinner om emnet:

https://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/04/18/on-the-liberal-bias-of-facts/

“The facts have a well-known liberal bias,” declared Rob Corddry way back in 2004 — and experience keeps vindicating his joke. But why?

Not long ago Ezra Klein cited research showing that both liberals and conservatives are subject to strong tribal bias — presented with evidence, they see what they want to see. I then wrote that this poses a puzzle, because in practice liberals don’t engage in the kind of mass rejections of evidence that conservatives do. The inevitable response was a torrent of angry responses and claims that liberals do too reject facts — but none of the claims measured up.

Just to be clear: Yes, you can find examples where *some* liberals got off on a hobbyhorse of one kind or another, or where the liberal conventional wisdom turned out wrong. But you don’t see the kind of lockstep rejection of evidence that we see over and over again on the right. Where is the liberal equivalent of the near-uniform conservative rejection of climate science, or the refusal to admit that Obamacare is in fact reaching a lot of previously uninsured Americans?

What I tried to suggest, but maybe didn’t say clearly, is that the most likely answer lies not so much in the character of individual liberals versus that of individual conservatives, as in the difference between the two sides’ goals and institutions. And Jonathan Chait’s recent thoughts on the inherently partisan nature of “data-based” journalism are, I think, helpful in bringing this better into focus.

As Chait says, the big Obamacare comeback and the reaction of the right are a very good illustration of the forces at work.

The basic facts here are that after a very slow start due to the healthcare.gov debacle, almost everything has gone right for reform. A huge surge of enrollments more than made up the initially lost ground; the age mix of enrollees has improved; multiple independent surveys have found a substantial drop in the number of Americans without health insurance.

Opponents of Obamacare could respond to these facts by arguing that the whole thing is nonetheless a bad idea, or they could accept that the rollout has gone OK but call for major changes in the program looking forward. What they’re actually engaged in, however, is mass denial and conspiracy theorizing strongly reminiscent of their reaction to polls showing Mitt Romney on the way to defeat, or for that matter evidence of climate change. Acceptance of the facts is, well, unacceptable.

Nothing illustrated this better than the reaction to Ezra Klein’s own note about the resignation of Kathleen Sebelius, which was intended as analysis rather than advocacy; Klein simply made the fairly obvious point that the HHS secretary was in effect free to resign now because Obamacare has been turned around and is going well. But Klein’s statement was met with a mix of outrage and ridicule on the right; how dare he suggest that the program was succeeding?

Why is it, then, that the right treats statements of fact as proof of liberal bias?

Chait’s answer, which I agree is part of the story, is that the liberal and conservative movements are not at all symmetric in their goals. Conservatives want smaller government as an end in itself; liberals don’t seek bigger government per se — they want government to achieve certain things, which is quite different. You’ll never see liberals boasting about raising the share of government spending in GDP the way conservatives talk proudly about bringing that share down. Because liberals want government to accomplish something, they want to know whether government programs are actually working; because conservatives don’t want the government doing anything except defense and law enforcement, they aren’t really interested in evidence about success or failure. True, they may seize on alleged evidence of failure to reinforce their case, but it’s about political strategy, not genuine interest in the facts.

One side consequence of this great divide, by the way, is the way conservatives project their own style onto their opponents — insisting that climate researchers are just trying to rationalize government intervention, that liberals like trains because they destroy individualism.

But this can’t be the whole story. It doesn’t explain, for example, the rejection of polls in 2012, or the refusal of the right to admit that things weren’t going well in Iraq — both cases in which conservatives really did have an interest in the outcomes. So what else differentiates the two sides?

Well, surely another factor is the lack of a comprehensive liberal media environment comparable to the closed conservative universe. If you lean right, you can swaddle yourself 24/7 in Fox News and talk radio, never hearing anything that disturbs your preconceptions. (If you were getting your “news” from Fox, you were told that the hugely encouraging Rand survey was nothing but bad news for Obamacare.) If you lean left, you might watch MSNBC, but the allegedly liberal network at least tries to make a distinction between news and opinion — and if you watch in the morning, what you get is right-wing conspiracy theorizing more or less indistinguishable from Fox.

Yet another factor may be the different incentives of opinion leaders, which in turn go back to the huge difference in resources. Strange to say, there are more conservative than liberal billionaires, and it shows in think-tank funding. As a result, I like to say that there are three kinds of economists: Liberal professional economists, conservative professional economists, and professional conservative economists. The other box isn’t entirely empty, but there just isn’t enough money on the left to close the hack gap.

Finally, I do believe that there is a difference in temperament between the sides. I know that it doesn’t show up in the experiments done so far, which show liberals and conservatives more or less equally inclined to misread facts in a tribal way. But such experiments may not be enough like real life to capture the true differences — although I’d be the first to admit that I don’t have solid evidence for that claim. I am, after all, a liberal.- Ble medlem

- 05.02.2015

- Innlegg

- 2.954

- Antall liker

- 316

Det kom da tydelig frem i valgkampen at CNN var for Hillary og det var av grunnene til at kanalen har navnet Clinton Network News, de burde ha beholdt navnet Chicken Noodle News

Det er ikke bare Trump som reagerte mot CNNIn October 2016, WikiLeaks published emails from John Podesta which showed CNN contributor Donna Brazile passing the questions for a CNN-sponsored debate to the Clinton campaign.[19] In the email, Brazile discussed her concern of Clinton's ability to field a question regarding the death penalty. The following day Clinton would receive the question about the death penalty, verbatim from an audience member at the CNN-hosted Town Hall event.[20] According to a CNNMoney investigation, the debate moderator Roland Martin of TV One "did not deny sharing information with Brazile."[21] CNN severed ties with Brazile on October 14, 2016.[22][23]

CNN anchor Chris Cuomo said on a live coverage of the 2016 elections that downloading the Podesta emails from the Wikileaks website was illegal, and that only the media could legally do so. The statement drew criticism to the network for being false.

On December 2, 2016, CNN made headlines on The Drudge Report when video obtained by FTVLive captured off camera audio of a CNN producer making a joke about Trump's plane crashing. The joke was made to CNN correspondent Suzanne Malveaux while she was being prepped to go live at the Trump Carrier press conference in Indiana

On January 10, 2017 CNN reported on the existence of classified documents that said Russia had compromising personal and financial information about then President-elect Donald Trump. CNN did not publish the dossier, or any specific details of the dossier, as they could not be verified. Later that day, BuzzFeed published the entire 35-page dossier with a disclaimer that it was unverified and "includes some clear errors".[30][31][32] The dossier had been read widely by political and media figures in Washington, and had been sent to multiple other journalists who had declined to publish it as it was unsubstantiated.[30] At a press conference the following day, Trump referred to CNN as fake news and refused to take a question from CNN reporter Jim Acosta.[33]

On February 24, 2017, CNN and other media organizations such as The New York Times were blocked from a White House press briefing. The network responded in a statement: "Apparently this is how they retaliate when you report facts they don't like. We'll keep reporting regardless."

On April 3, 2016, hundreds of supporters of Bernie Sanders protested outside of CNN Los Angeles. Sanders supporters were protesting CNN's coverage of the 2016 United States presidential elections, specifically in regards to the lack of airtime Sanders has received. Known as Occupy CNN, protesters claimed that major media networks have intentionally blacked out Sanders' presidential campaign in favor of giving much more airtime to candidates such as Hillary Clinton.[18]- Ble medlem

- 28.09.2016

- Innlegg

- 13.480

- Antall liker

- 15.513

Det kan virke på meg som om du finner saklig uenighet problematisk. At også Sanders' tilhengere reagerer på CNN's formidling av et eller annet, kan også bety at de faktisk gjør et ærlig forsøk på å fremstille saker relativt balansert. Det er i utgangspunktet umulig å gjøre alle fornøyd, noen vil alltid mene at fremstillingen er feil på et eller annet vis.....Det er ikke bare Trump som reagerte mot CNN.....

Enkelte fakta er greie å vise til, koster en bussbillett eller et jagerfly en eller annen pris, kan man vise regningen, og fakta er på bordet. Man kan også vise analyser av det som kommer ut av en jetmotor, og bevise at de hvite stripene er vann, men allerede med noe som er så lett verifiserbart, setter en del folk i gang å ralle om "fake news", og skaper seg heller en morsom konspirasjonsteori som virker mye mer plausibel enn virkeligheten... Men det er uansett ikke "fake news" at de hvite stripene bak flyene stort sett er vann, selv om noen påstår det.

Så kommer de mer vanskelige fakta, for hvor mye koster en motorvei? En eller annen sum kostet det å bygge den. Men så kommer en faginstans på banen og sier at den sparer samfunnet for 260 mill pr. år. grunnet mindre kø. Dette er et vanskelig regnestykke. Lettere blir det ikke når en annen faginstans fremlegger at grunnet økt trafikk på den nye veien, så øker forurensningen, og dette koster samfunnet 100 mill. pr. år. Så sier forrige faginstans at vi også sparer 43 mill. pr. år fordi ulykkesantallet gikk ned. Og sånn kan vi fortsette.

Politikerne må ta stilling til alle disse forsøksvis faktabaserte regnestykkene, og tolke dem i et politisk verdensbilde, og argumentere for sitt syn. At Frp legger mest vekt på samfunnets transportbehov, mens Sv bare snakker om forurensningen som skapes, gjør ingen av dem til løgnere, de leverer kun tolkninger av virkeligheten, sett gjennom sine fargede briller.

Trump, derimot, lyver, både fordi han vil det (bevisst løgn), fordi han ikke forstår hva han prater om, og, fordi han ikke alltid evner å forstå overgangen mellom virkelighet og fantasi. Han bedriver noe helt annet enn den jevne politiker, og han behøver ikke hjelp av CNN eller annen presse for å vise det. CNN er ikke like nøytral som BBC, men antakelig noe mer nøytrale enn FOX, så får vi bare forsøke å leve med dette, da, og farge innholdet litt med våre egne briller, til det blir sånn passe.

Uansett nytter det ikke å flytte fokus så enormt mye at man ikke forstår at vi har å gjøre med tidenes mest udugelige, demokratisk valgte president.

DisqutabelSist redigert:

Hvis en ser på Politifact sine målinger av politikere i USA, så ser en at den gjengse politiker ligger fra 35-50% utsagn som går fra hovedsakelig feil. til feil, og "fyr i buksa" - det være seg demokrater eller republikanere. Det er noen få unntak som ligger lavere, og så har du de rabiate radiovertene med følge som ligger langt over. Politisk syn vil alltid farge verdenssynet og hvilke fakta en vektlegger, slik at det vil neppe være noen politikere som bare snakker 100% sannhet. Hvis en politiker ligger mellom 25-30% på feil-siden skal en være svært fornøyd.Politikerne må ta stilling til alle disse forsøksvis faktabaserte regnestykkene, og tolke dem i et politisk verdensbilde, og argumentere for sitt syn. At Frp legger mest vekt på samfunnets transportbehov, mens Sv bare snakker om forurensningen som skapes, gjør ingen av dem til løgnere, de leverer kun tolkninger av virkeligheten, sett gjennom sine fargede briller.

Disqutabel

Johan-Kr

Holder han virkelig løftene sine når det gjelder "health care"?Nå holder Trump lovnaden om Obamacare, dere kritiserer han for det også, er dere aldri fornøyd

Dette er hva han sa i valgkampen:

"I was the first & only potential GOP candidate to state there will be no cuts to Social Security, Medicare & Medicaid."

og

"I am going to take care of everybody. I don't care if it costs me votes or not. The government's gonna pay for it."

Kan du med hånden på hjerte si at det kommer til å skje i den nye "helsereformen" til Trump?

Du har uansett satt deg i en situasjon der han anses som din store helt siden du stadig forsvarer en som knapt har sagt et sant ord siden han ble innsatt.

Tja, han juger ikke mer enn politikere flest, og for 4 gang, han er ikke min helt men jeg koser meg med å se den råtne media og de politiske korrekte dumme seg ut gang på gang.

Sett i lys av hvor ofte helten din juger, misoppfatter og forvrenger virkeligheten er det nok smart å telle disse tilfelleneTrump hadde rett igjen:

Nå må du forstå at greia med Trump er ikke at han er så bra, det er bare det at hatet til alle andre er så mye sterkere. Konstruktive alternativer er ikke så viktig bare man river med elendigheten og sparker alle andre ett visst sted. Så hva Trump kommer opp med er ikke viktig bare han river ned råttenskapen. I den konteksten er det litt sjarmerende, og ikke så lite avslørende, at det er alle vi andre som er "haters". Men for å forstå dette, kreves det selvsagt litt selvinnsikt.

Holder han virkelig løftene sine når det gjelder "health care"?Nå holder Trump lovnaden om Obamacare, dere kritiserer han for det også, er dere aldri fornøyd

Dette er hva han sa i valgkampen:

"I was the first & only potential GOP candidate to state there will be no cuts to Social Security, Medicare & Medicaid."

og

"I am going to take care of everybody. I don't care if it costs me votes or not. The government's gonna pay for it."

Kan du med hånden på hjerte si at det kommer til å skje i den nye "helsereformen" til Trump?665finger

Gjest

det å klage på mediebedrifter er helt normalt fjernis. Det at et statsoverhode gjør det i et demokratisk land det er svært uvanlig. Er du amerikansk statsborger? Eller bare henger du deg på sjargongen til laget ditt? Du bruker begreper som lefties. Hvorfor er en amerikansk journalist "lefty" ? Nevn de 5 viktigste politiske sakene som skiller en " lefty" fra laget ditt(les trump og co)Det kom da tydelig frem i valgkampen at CNN var for Hillary og det var av grunnene til at kanalen har navnet Clinton Network News, de burde ha beholdt navnet Chicken Noodle News

Det er ikke bare Trump som reagerte mot CNNIn October 2016, WikiLeaks published emails from John Podesta which showed CNN contributor Donna Brazile passing the questions for a CNN-sponsored debate to the Clinton campaign.[19] In the email, Brazile discussed her concern of Clinton's ability to field a question regarding the death penalty. The following day Clinton would receive the question about the death penalty, verbatim from an audience member at the CNN-hosted Town Hall event.[20] According to a CNNMoney investigation, the debate moderator Roland Martin of TV One "did not deny sharing information with Brazile."[21] CNN severed ties with Brazile on October 14, 2016.[22][23]

CNN anchor Chris Cuomo said on a live coverage of the 2016 elections that downloading the Podesta emails from the Wikileaks website was illegal, and that only the media could legally do so. The statement drew criticism to the network for being false.

On December 2, 2016, CNN made headlines on The Drudge Report when video obtained by FTVLive captured off camera audio of a CNN producer making a joke about Trump's plane crashing. The joke was made to CNN correspondent Suzanne Malveaux while she was being prepped to go live at the Trump Carrier press conference in Indiana

On January 10, 2017 CNN reported on the existence of classified documents that said Russia had compromising personal and financial information about then President-elect Donald Trump. CNN did not publish the dossier, or any specific details of the dossier, as they could not be verified. Later that day, BuzzFeed published the entire 35-page dossier with a disclaimer that it was unverified and "includes some clear errors".[30][31][32] The dossier had been read widely by political and media figures in Washington, and had been sent to multiple other journalists who had declined to publish it as it was unsubstantiated.[30] At a press conference the following day, Trump referred to CNN as fake news and refused to take a question from CNN reporter Jim Acosta.[33]

On February 24, 2017, CNN and other media organizations such as The New York Times were blocked from a White House press briefing. The network responded in a statement: "Apparently this is how they retaliate when you report facts they don't like. We'll keep reporting regardless."

On April 3, 2016, hundreds of supporters of Bernie Sanders protested outside of CNN Los Angeles. Sanders supporters were protesting CNN's coverage of the 2016 United States presidential elections, specifically in regards to the lack of airtime Sanders has received. Known as Occupy CNN, protesters claimed that major media networks have intentionally blacked out Sanders' presidential campaign in favor of giving much more airtime to candidates such as Hillary Clinton.[18]HHardingfele

Gjest

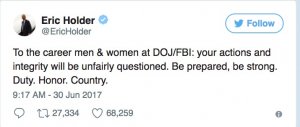

Her om dagen sendte Eric Holder ut følgende melding til ansatte ved Department of Justice og FBI (tidligere sjef for DOJ):

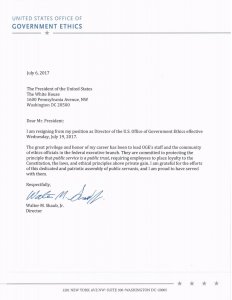

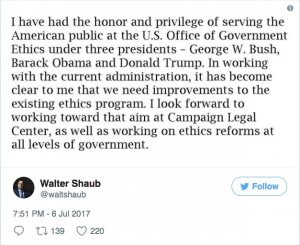

Idag leverte sjefen for kontoret med ansvar for at statsansatte ikke beriker seg inn sin avskjed. Han kan ikke innestå for hvordan Trump-administrasjonen holder på og vil ikke stå ansvarlig.

Shaub forklarte sin beslutning til pressen og i denne meldingen:

H

HHardingfele

Gjest

– What level Crazy Uncle do you want?

– Titanium grade crazy.

– OK.

Film i linken:

https://twitter.com/cbsnews/status/883018777708953600

Liksom ikke noe poeng i at de kvitter seg med Donalden.G

Liksom ikke noe poeng i at de kvitter seg med Donalden.GGjestemedlem

Gjest

Litt mer om hvordan Trumps team er kjøpt og styrt av særinteressegrupper.

http://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/06/business/dealbook/massachusetts-betsy-devos-lawsuit.html

Democratic attorneys general from 18 states and the District of Columbia filed a lawsuit on Thursday against the Education Department and its secretary, Betsy DeVos, challenging the department’s move last month to freeze new rules for erasing the federal loan debt of student borrowers who were cheated by colleges that acted fraudulently.

--

Men Trump har jo selv en historie med å svindle studenter med falske studier på donaldskoler.- Ble medlem

- 05.02.2015

- Innlegg

- 2.954

- Antall liker

- 316

Legger ut en link til hele den fantastiske talen til Trump som han hadde i Polen i går.

https://www.document.no/2017/07/07/president-trumps-speech-at-kasinski-square/- Ble medlem

- 28.09.2016

- Innlegg

- 13.480

- Antall liker

- 15.513

Rent nasjonalistisk sprøyt fra ende til annen. Og selv om talen neppe er skrevet av presidenten selv, kunne en hver nogenlunne belest syvendeklassing laget noe like "fantastisk". Dette er prototypen på nettopp den type taler menneskeheten ikke behøver i 2017.Legger ut en link til hele den fantastiske talen til Trump som han hadde i Polen i går.

https://www.document.no/2017/07/07/president-trumps-speech-at-kasinski-square/

DisqutabelSelvfølgelig var ikke denne talen skrevet av Donald selv. Den inneholdt navn på personer han neppe har hørt om i tillegg til setninger med mere enn 5 ord. Og innholdet var helt fjernis fra konsistens hvor "awesome" den enn måtte fremstå for noen.HHardingfele

Gjest

Den talen hørte jeg live. Som fusker i propagandafaget var det ikke vanskelig å forstå oppbygning, formål og tiltenkt publikum. Derfor er det heller ingen overraskelse at fjernis og dokument.no tok av på talen. Det var meningen.

Var den fantastisk? Den er underlig. USA har store styrker stående i Tyskland, talen inneholdt lange passasjer om Hitler-Tysklands herjinger i Warsawa. Dagen etter skulle Trump møte med Merkel. Var det nødvendig med Jerusalem Avenue passasjene? Er det nyttig at USA har lagt seg i krig med Tyskland på statssjefplan, med en president som presenterer en hjemmesnekret NATO-regning til Merkel når hun kommer til ham; og samme president som sår splid mellom to NATO-allierte med en ti minutter lang detaljert beskrivelse av maskingeværild mot polske opprørere som vasset i blod på Jerusalem Avenue under 2. Store Slagsmål?

Det spørs hva formålet er. Trump sier at vestlig sivilisasjon vil bukke under pga mangel på vilje til innsats og vilje til offer. Som vanlig er trusselen dramatisk overdrevet og vestlig motstandsstyrke dramatisk "underdrevet". Typisk ekstrem høyresidesvada som slukes rått. Militæret kan aldri bli for stort, offerviljen ditto. Til slutt er det 11-åringer og oldinger man sender i krig, når Berlin skal forsvares.

Vi må leve med at folk har ulike impulser og motiver, ulike ting de tror på. Autoritetstilbederne er faste i sin overbevisning og vingler sjelden unna den rette sti. De har ikke vært en trussel mot samfunnet i etterkrigstiden, fordi det gikk så jævla grundig til helvete sist Store Far politikerne fikk lov til å herje. Men det er kommet til nye generasjoner, historien er fusket til og folk har glemt hvordan Europa så ut i 1946.

Lykke til, fjernis.

Alt som mangler er Horst Wessel Lied.

We can have the largest economies and the most lethal weapons anywhere on Earth, but if we do not have strong families and strong values, then we will be weak and we will not survive. (Applause.) If anyone forgets the critical importance of these things, let them come to one country that never has. Let them come to Poland. (Applause.) And let them come here, to Warsaw, and learn the story of the Warsaw Uprising.

When they do, they should learn about Jerusalem Avenue. In August of 1944, Jerusalem Avenue was one of the main roads running east and west through this city, just as it is today.

Control of that road was crucially important to both sides in the battle for Warsaw. The German military wanted it as their most direct route to move troops and to form a very strong front. And for the Polish Home Army, the ability to pass north and south across that street was critical to keep the center of the city, and the Uprising itself, from being split apart and destroyed.

Every night, the Poles put up sandbags amid machine gun fire — and it was horrendous fire — to protect a narrow passage across Jerusalem Avenue. Every day, the enemy forces knocked them down again and again and again. Then the Poles dug a trench. Finally, they built a barricade. And the brave Polish fighters began to flow across Jerusalem Avenue. That narrow passageway, just a few feet wide, was the fragile link that kept the Uprising alive.

Between its walls, a constant stream of citizens and freedom fighters made their perilous, just perilous, sprints. They ran across that street, they ran through that street, they ran under that street — all to defend this city. «The far side was several yards away,» recalled one young Polish woman named Greta. That mortality and that life was so important to her. In fact, she said, «The mortally dangerous sector of the street was soaked in the blood. It was the blood of messengers, liaison girls, and couriers.»

Nazi snipers shot at anybody who crossed. Anybody who crossed, they were being shot at. Their soldiers burned every building on the street, and they used the Poles as human shields for their tanks in their effort to capture Jerusalem Avenue. The enemy never ceased its relentless assault on that small outpost of civilization. And the Poles never ceased its defense.

The Jerusalem Avenue passage required constant protection, repair, and reinforcement, but the will of its defenders did not waver, even in the face of death. And to the last days of the Uprising, the fragile crossing never, ever failed. It was never, ever forgotten. It was kept open by the Polish people.

The memories of those who perished in the Warsaw Uprising cry out across the decades, and few are clearer than the memories of those who died to build and defend the Jerusalem Avenue crossing. Those heroes remind us that the West was saved with the blood of patriots; that each generation must rise up and play their part in its defense — (applause) — and that every foot of ground, and every last inch of civilization, is worth defending with your life.

Our own fight for the West does not begin on the battlefield — it begins with our minds, our wills, and our souls. Today, the ties that unite our civilization are no less vital, and demand no less defense, than that bare shred of land on which the hope of Poland once totally rested. Our freedom, our civilization, and our survival depend on these bonds of history, culture, and memory.Sist redigert av en moderator:Ganske ok samtale med Naomi Klein:

https://www.theguardian.com/global/...trump-is-more-like-the-schlock-doctrine-video

Bak Trump har republikanerne a field day.Formålet er selvsagt å svekke EU som er en effektiv og mektig forhandlings- og reguleringsmotpart mot at Donalds venner, regjeringskolleger samt div TeaParty støttespillere kan fylle sine skattekister ytterligere. I det spillet gjelds det å svekke styret i Washington, samt andre internasjonale parter som kan legge hindre i veien. Putin og de nasjonalreaksjonære i Polen og Ungarn er effektive støttespillere i den prosessen. Follow the money, fela.

Og folk som er historieløse svelger selvsagt agnet rått. Det Nato, EU og internasjonale handelsregime som har sørget for at Polen for første gang i noenlunde moderne tid har fått være i fred, og har opplevd en økonomisk fremgang nesten uten sidestykke, er nå plutselig den store fienden. Nasjonalisme er snodige saker, og mange har gjennom årene visst å puste til den for å fremme egen sak. Sporene skremmer, for de som gidder å se lenger enn egen nese.Sist redigert:- Ble medlem

- 05.02.2015

- Innlegg

- 2.954

- Antall liker

- 316

Demokratene må jo være total gale, ordføreren i New York drar til Tyskland for å demonstrere mot sin egen president, og så folkelig disse demonstrantene er.

Kanskje på tide at USA får byttet ut resten av politikerne fra Bush og Obama tiden.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/arti...urprise-trip-to-join-trump-protest-in-germanyNew York Mayor Bill de Blasio is headed to Hamburg, Germany on Saturday to be a keynote speaker at a demonstration against President Donald Trump’s policies and the growth of right-wing populist movements in Europe.

Heia Trump.- Ble medlem

- 05.02.2015

- Innlegg

- 2.954

- Antall liker

- 316

Eu ødelegger seg selv, innvandringen og diktatur styret fra Brussel ordner det.Formålet er selvsagt å svekke EU som er en effektiv og mektig forhandlings- og reguleringsmotpart mot at Donalds venner, regjeringskolleger samt div TeaParty støttespillere kan fylle sine skattekister ytterligere. I det spillet gjelds det å svekke styret i Washington, samt andre internasjonale parter som kan legge hindre i veien. Putin og de nasjonalreaksjonære i Polen og Ungarn er effektive støttespillere i den prosessen. Follow the money, fela.

Og folk som er historieløse svelger selvsagt agnet rått. Det Nato, EU og internasjonale handelsregime som har sørget for at Polen for første gang i noenlunde moderne tid har fått være i fred, og har opplevd en økonomisk fremgang nesten uten sidestykke, er nå plutselig den store fienden. Nasjonalisme er snodige saker, og mange har gjennom årene visst å puste til den for å fremme egen sak. Sporene skremmer, for de som gidder å se lenger enn egen nese.- Status

- Stengt for ytterligere svar.

-

Laster inn…

Diskusjonstråd Se tråd i gallerivisning

-

-

Laster inn…