Whenever Tyrone moves into a new apartment, he lies down naked on his living room floor.

It’s a ritual, a reminder of the years he spent without a floor underneath him or a ceiling above. He was homeless for four years in Georgia: sleeping on benches, biking to interviews in the heat, arriving an hour early so he wouldn’t be sweaty for the handshake. When he finally got a job, his co-workers found out that he washed himself in gas station bathrooms and made him so miserable he quit. “They said I ‘smelled homeless,’” he says.

Tyrone moved to Seattle six years ago, when he was 23, because he’d heard the minimum wage there was almost double what he made in Atlanta. He got a job at a grocery store and slept in a shelter while he saved. Since then, his income has gone up, but he’s been pushed farther and farther from the city. First stop was subsidized housing in Kirkland, 20 minutes east across the lake. Then a rented house in Tacoma, 45 minutes south, sharing a bedroom with his girlfriend and, eventually, a son. The breakup is why he’s now in Lakewood, even farther south, in a one-bedroom right next to a freeway entrance.

And it’s already such a strain. Tyrone earns $17 an hour as a security guard at a building site, his highest wage ever. But he’s a contractor (of course), so he doesn’t get sick leave or health insurance. His rent is $1,100 a month. It’s more than he can afford, but he could only find one building that would let him move in without paying the full deposit in advance.

Since rent is due on the 1st and he gets paid on the 7th, his landlord adds a $100 late fee to each month’s bill. After that and the car payments—it’s a two-hour bus ride from the suburb where he lives to the suburb where he works—he has $200 left over every month for food. The first time we met, it was the 27th of the month and Tyrone told me his account was already zeroed out. He had pawned his skateboard the previous night for gas money.

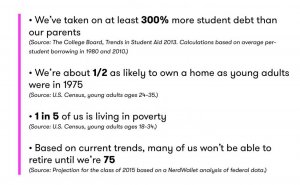

Despite the acres of news pages dedicated to the narrative that millennials refuse to grow up, there are twice as many young people like Tyrone—living on their own and earning less than $30,000 per year—as there are millennials living with their parents. The crisis of our generation cannot be separated from the crisis of affordable housing.

More people are renting homes than at any time since the late 1960s. But in the 40 years leading up to the recession, rents increased at more than twice the rate of incomes. Between 2001 and 2014, the number of “severely burdened” renters—households spending over half their incomes on rent—grew by more than 50 percent. Rather unsurprisingly, as housing prices have exploded, the number of 30- to 34-year-olds who own homes has plummeted.