Og omtrent hvor ser du noe ulovlig i dette? Mobilisering av stemmeberettigede til å benytte stemmeretten og en «public awareness campaign» for å forklare folk hvordan valgsystemet fungerer - hvilken konspirasjon! Mye bedre at de har no frickin’ clue og sluker rått hva Trump enn finner på å si den dagen, liksom?

Politikk, religion og samfunn President Donald J. Trump - Quo vadis? (Del 2)

- Trådstarter Høvdingen

- Startdato

Diskusjonstråd Se tråd i gallerivisning

-

om mob og mob og mob. ikke all mob er lik andre mobber.

The Democratic Party Has a Fatal Misunderstanding of the QAnon Phenomenon

Their belief that this surreal conspiracy has arisen because of the poor education of its adherents is based in classism, not reality.

On Thursday, the House voted to strip Georgia Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene of her committee assignments, putting an end to one chapter of what’s sure to be an ongoing saga in the chamber’s Republican caucus. In a meandering nonapology in the hours before the vote, Greene, who has endorsed an impressive array of conspiracy theories, including QAnon and claims that Hillary Clinton had raped, mutilated, and consumed the blood of a child, characterized negative coverage of her as—surprise, surprise—more “cancel culture” run amok. While Greene’s rise bodes poorly for the country, some have already decided her newfound celebrity is good news for the Democratic Party’s electoral prospects. On Tuesday, Politico reported that the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee intends to focus on QAnon in its messaging, ahead of the 2022 midterms, in the hopes that the specter of more Greenes in Congress will push more people away from the GOP. “They can do QAnon, or they can do college-educated voters,” DCCC Chair Sean Patrick Maloney said. “They cannot do both.”

Actually, they can. Trying to tether the GOP more tightly to the extremism it’s cultivated makes sense, and the strategy may help prevent some moderate suburbanites from returning to the party’s inordinately big tent. But polls have shown few differences on QAnon between voters with and without college degrees—Civiqs’s latest survey, for instance, registers 72 percent opposition and 5 percent support for the theory among graduates. The split is 71 to 5 among nongraduates and 78 to 3 among postgraduates. And, notably, Americans without college degrees are less likely than graduates to have heard of QAnon in the first place. If this is a surprise, consider the fact that Greene herself went to college. And when she runs for reelection next year, she’s sure to enjoy the support of many college-educated Republicans who, whether they personally believe in QAnon or not, want to keep as many right-wing firebrands as they can in Congress. Those who think such voters will inevitably doom the party would do well to remember the 2010 midterms—despite the Tea Party’s rhetoric and antics, Republicans took the House in a historic wave.

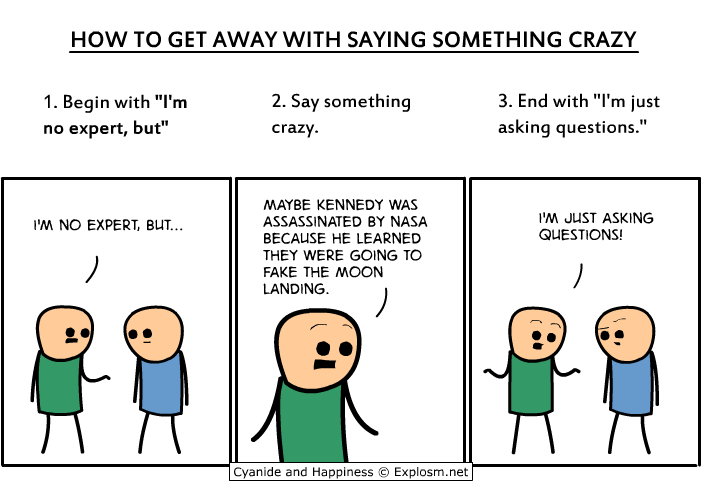

Of all the “big lies” distorting our politics, one of the largest and most popular—back in 2010 and now—has been the notion that our political divisions are the product of under- or miseducation. The Republican Party’s flight into lunacy, it’s often suggested, has a fairly simple cause. The unwashed aren’t getting The Facts in school or from their media sources, and it’s up to the enlightened to shower The Facts upon them—perhaps, as some “disinformation” experts recently suggested to The New York Times, with a “reality czar” at the White House manning the hose. This was the explanation many turned to as the Trump era began, and it was the explanation many turned to for how it ended. Take the remarkable lede that topped a piece from The Atlantic’s Caitlin Flanagan on the Capitol rioters last month:

«Here they were, a coalition of the willing: deadbeat dads, YouPorn enthusiasts, slow students, and MMA fans. They had heard the rebel yell, packed up their Confederate flags and Trump banners, and GPS-ed their way to Washington. After a few wrong turns, they had pulled into the swamp with bellies full of beer and Sausage McMuffins, maybe a little high on Adderall, ready to get it done.»

This week, The Atlantic published what amounted to a rebuttal. According to court records and media coverage reviewed by the University of Chicago’s Robert Pape and the Chicago Project on Security and Threats’ Keven Ruby, a full 40 percent of the 193 people charged with breaking into the Capitol grounds were business owners or white-collar workers. “Unlike the stereotypical extremist, many of the alleged participants in the Capitol riot have a lot to lose,” they wrote. “They work as CEOs, shop owners, doctors, lawyers, IT specialists, and accountants.”

There were plenty of graduates and good students in the mob that day. Plenty of dropouts and poor students looked on in horror. And as much as the right’s critics might prefer an understanding of what’s happened to our politics that flatters their intelligence, the challenge we’re facing isn’t that millions of hapless and benighted yokels have been bamboozled by disinformation. It’s that millions of otherwise ordinary people from many walks of life—including many who went to and even excelled in college—have a material or ideological interest in keeping the Democratic Party and its voters from power by any means possible. And those means include the utilization of narratives, including conspiracy theories, that delegitimize Democrats and offer hope of their eventual comeuppance.

Those theories are being fueled by politically motivated reasoning, and the literature on this is now fairly vast. For a prescient paper published in the American Journal of Political Science just a month before the 2016 presidential election, the University of Minnesota’s Joanne Miller and Christina Farhart and Colorado State University’s Kyle Saunders conducted a survey examining support for conspiracy theories, including birtherism and 9/11 trutherism. In a result unsurprising to those who follow this research, they found that higher levels of political knowledge actually deepened the likelihood that conservatives with low trust in people and major institutions would endorse right-wing conspiracy theories. In a section reviewing previous research on the subject, the authors explained that political sophisticates “have the ability to make connections between abstract principles and more concrete attitudes and are therefore more fully able to notice the implications of specific attitudes for their worldviews.” “Because politically knowledgeable people care more about politics and hold stronger political attitudes,” they added, “they are especially likely to want to protect those attitudes.”

This dynamic is now well established across multiple issue areas. Studies have suggested, for example, that higher levels of political knowledge, scientific knowledge, and quantitative skill can actually deepen disagreements about climate change and gun control. And researchpublished by Harvard’s Kennedy School last spring found no correlation between educational attainment and beliefs in conspiracy theories about the coronavirus pandemic—indicating, the authors wrote, that the beliefs were “not merely the product of deficient health education” and had been fed by “psychological and political motivations.” The popularity of the idea that simple ignorance lies at the heart of all this may itself be proof of the phenomenon these studies point to: Many people will believe what they want to believe in spite of available data and evidence.

There isn’t much to be done about any of this: We won’t do away with motivated reasoning without wholly reinventing human beings; we can’t contain the spread of disinformation without wholly reinventing the internet and the media as we know them. And while the second task would be easier than the first, it doesn’t seem much more likely. Doing something about the power of the Republican Party seems more plausible—as long as those fighting it frame the battle as right against wrong rather than smart against dumb.

Democrats should try campaigning on the truth: The Republican Party is controlled by intelligent, college-educated, and affluent elites who concoct dangerous nonsense to paper over a bigoted, plutocratic agenda and to justify attacks on the democratic process. That agenda and those attacks are supported by millions of reasonably intelligent voters who will believe or claim to believe anything that furthers the objective of keeping conservatives in control of this country forever. Simply pointing to figures like Greene and hoping the indignation of college graduates will do the rest is a mistake. Instead, Democrats should present voters with a material choice between a party that has nothing to offer the majority of Americans but abuse and conspiratorial flimflam and a party committed to building a democracy and an economy that work for all. If they don’t, the lizard people who run the GOP will be running the government again in no time.

Osita Nwanevu @OsitaNwanevu

Osita Nwanevu is a staff writer at The New Republic.

[min uth.]

The Democratic Party Has a Fatal Misunderstanding of the QAnon Phenomenon

Their belief that this surreal conspiracy has arisen because of the poor education of its adherents is based in classism, not reality. newrepublic.com

Sist redigert:

newrepublic.com

Sist redigert:- Ble medlem

- 23.03.2006

- Innlegg

- 19.948

- Antall liker

- 10.456

Det må da være mulig å diskutere hvordan man skal forholde seg til IS-terrorister og samtidig begynne å forstå dem uten at man unnskylder dem en meter.Det må da være mulig å diskutere hvordan man skal forholde seg til IS-terrorister også uten å skulle begynne å forstå dem ihjel med alle mulige forklaringer av alt som er skjevt og skakt i vestlige samfunn. Joda, sikkert, men det unnskylder dem ikke en meter.

Har du lest det du lenker til? Det står:hevder at det helt klart var en sammensvergelse på venstre-siden med urent trav.

"a vast, cross-partisan campaign to protect the election–an extraordinary shadow effort dedicated not to winning the vote but to ensuring it would be free and fair, credible and uncorrupted."

Det er ikke venstresida som får skylden, og det artikkelen mener har skjedd er ikke et forsøk på å hive ut Trump for enhver pris, men å "sikre et fritt, rettferdig, troverdig og ukorrumpert valg".

Noen flere utvalgte sitater:

"Though much of this activity took place on the left, it was separate from the Biden campaign and crossed ideological lines, with crucial contributions by nonpartisan and conservative actors."

"The scenario the shadow campaigners were desperate to stop was not a Trump victory. It was an election so calamitous that no result could be discerned at all, a failure of the central act of democratic self-governance that has been a hallmark of America since its founding."

"They fended off voter-suppression lawsuits, … successfully pressured social media companies to take a harder line against disinformation and used data-driven strategies to fight viral smears. They executed national public-awareness campaigns that helped Americans understand how the vote count would unfold over days or weeks, preventing Trump’s conspiracy theories and false claims of victory from getting more traction. After Election Day, they monitored every pressure point to ensure that Trump could not overturn the result."

"Trump and his allies were running their own campaign to spoil the election."

"“Every week, we felt like we were in a struggle to try to pull off this election without the country going through a real dangerous moment of unraveling,” says former GOP Representative Zach Wamp, a Trump supporter who helped coordinate a bipartisan election-protection council."

"This is the inside story of the conspiracy to save the 2020 election"

Gidder ikke finne flere, men dette er altså en historie om at noen aktivister gikk inn for å styrke demokratiske institusjoner for å sikre et rettferdig valg.

Du må lære deg å juge bedre.Ja, de har ulike sider av saken, poenget er at de peker på at det også helt klart var en rigging mot Trump, og er derfor svært bra da den balanserer opp mye av de urettmessige beskyldningene mot høyre-siden, og som også er litt for ensidig her inne. Det var mye snusk på venstresiden også. Mer vil komme for dagen etterhvert.

forklarJa, de har ulike sider av saken, poenget er at de peker på at det også helt klart var en rigging mot Trump, og er derfor svært bra da den balanserer opp mye av de urettmessige beskyldningene mot høyre-siden, og som også er litt for ensidig her inne. Det var mye snusk på venstresiden også. Mer vil komme for dagen etterhvert.- Ble medlem

- 23.03.2006

- Innlegg

- 19.948

- Antall liker

- 10.456

Enkelt, Trump vant ikke som de hadde forventet. Da må valget være rigget.forklar

Anbefaler deg å lese artikkelen, den er spennende og interessant og handler om noe helt annet enn du tror.Jo, de har ulike sider av saken, poenget er at de peker på at det også helt klart var en rigging mot Trump, og er derfor svært bra da den balanserer opp mye av de urettmessige beskyldningene mot høyre-siden, og som også er litt for ensidig her inne. Det var mye snusk på venstresiden også. Mer vil komme for dagen etterhvert.

Den sier selv at den handler om "a vast, cross-partisan campaign to protect the election–an extraordinary shadow effort dedicated not to winning the vote but to ensuring it would be free and fair, credible and uncorrupted".

På norsk: "en storstilt, tverrpolitisk kampanje for å beskytte valget – en ekstraordinær og skjult innsats som ikke var rettet mot å vinne valget, men å sikre at det skulle være fritt, rettferdig, troverdig og ukorrumpert."

Er dette en dårlig ting ifølge deg?

Neste setning: "For more than a year, a loosely organized coalition of operatives scrambled to shore up America’s institutions as they came under simultaneous attack from a remorseless pandemic and an autocratically inclined President."

På norsk: "I mer enn et år jobbet en løst sammensatt gruppe for å beskytte USAs institusjoner mens de ble angrepet både av en nådeløs pandemi og en autokratisk orientert president."

Skulle de latt være?

"The scenario the shadow campaigners were desperate to stop was not a Trump victory. It was an election so calamitous that no result could be discerned at all, a failure of the central act of democratic self-governance that has been a hallmark of America since its founding."

Eller: "Scenariet de forsøkte å stoppe var ikke at Trump skulle vinne valget. De forsøkte å unngå et valg som ville vært så katastrofalt gjennomført at det ville vært umulig å utrope en vinner. Det ville vært en total svikt av den sentrale mekanismen i det demokratiske selvstyret som har vært USAs kjennetegn siden grunnleggelsen."

Det er ikke rom for å tolke inn det du gjør her. Som sagt, jug bedre.Sist redigert:Hvordan man kan lese den artikkelen og få det til at det var en rigging av valget mot Trump er aldeles uforståelig. Det artikkelen beskriver er jo arbeidet som ble gjort nettopp for at det skulle være et fritt, demokratisk valg der hverken den ene eller den andre siden skulle kunne manipulere valget.

Her skorter det nok på leseforståelsen hos enkelte. Artikkelen hevder slettes ikke det som Armand68 antyder.

Men takk for lenken. Endelig en referanse til noe annet enn document og resett.Sist redigert:Hva får deg til å tro at folk med høyere utdanning omgås folk fra andre samfunnslag mer enn andre? For å ikke snakke om folk fra andre kulturer. Min erfaring er motsatt.

Jeg vet ikke om du leser feil med vilje eller ikke, men det jeg sa var faktisk at selve det å at en utdannelse uvegerlig innebærer en rekke nye opplevelser og erfaringer man ikke får ved å la være. Det jeg ikke sa et ord om er hvem og hva slags folk man omgås etter utdannelsen, siden det åpenbart kommer helt an på jobben.

Hva får deg til å tro at folk med høyere utdanning omgås folk fra andre samfunnslag mer enn andre? For å ikke snakke om folk fra andre kulturer. Min erfaring er motsatt.

Mens min ikke er det. Jeg vet ikke hvem du tenker på når du snakker om "folk med høyere utdanning", men kanskje du skal tenke gjennom hva begrepet "høyere utdanning" omfatter og hvor mange yrkesgrupper det inkluderer. For meg virker det omtrent som om du forestiller deg at det kun omfatter ting som advokater, embedsmenn og lignende.

Den farligste retorikken er åndssnobberiet og dets assosierte ekkokamre.

Fullstendig uenig. Det farligste er ekkokammer, punktum. For min del mener jeg at forestillingen om "eliter" som ikke skjønner bæret - den du tidvis liker å nøre opp under - er minst like farlig som forestillingen om den uutdannede bermen, siden langt flere abonnerer på den.

For ikke lenge siden var arbeiderklassen sett på som viktig og endog som noe edelt. Nå blir de sett ned på og kastet til ulvene

Tullprat. Og forestillingen om arbeiderklassen som noe edlere enn andre samfunnslag er like tett og destruktiv som den middelalderske forestilling om "The Noble Poor". Samfunnet trenger folk i alle typer posisjoner for å fungere. Den som vasker dassene på Oslo S eller henter søppelet ditt på xxxdager er like nødvendig og edel som dommeren som sender deg i kasjotten, eller banksjefen som avslår søknaden din om huslån, men ikke det spøtt mer.

Du insinuerer at de som ikke tar en slik utdanning går glipp av omgang mennesker fra andre samfunnslag, andre deler av landet, andre land og kulturer. Det finnes ingen belegg for. Selvfølgelig går du glipp av erfaringer ved ikke ta høyere utdanning, men det gjør du også dersom du velger å ta høyere utdanning i stedet for å gå rett i jobb. Andre erfainger - like verdifulle.Jeg vet ikke om du leser feil med vilje eller ikke, men det jeg sa var faktisk at selve det å at en utdannelse uvegerlig innebærer en rekke nye opplevelser og erfaringer man ikke får ved å la være.

Etter 20år innen akademia har jeg aldri møtt dette mangfoldet du omtaler. Tvert imot.

Jada ekkokamre er galt det, men det er enkelte ekkokamre som får mer fokus enn andre. Og jeg mener selvfølgelig ikke at arbeiderklassen er noe edelt, men illustrerer den store forandringen i hvordan vi omtaler dem.

Vi er alle like mye verdt, men vi blir ikke behandlet som om vi er det. Og slettes ikke av åndssnobber.....Sist redigert:

Synes det er litt trist at alle som er mot deg her inne ikke kommer med annet enn løgn ig de klager på alternativ mediaJa, de har ulike sider av saken, poenget er at de peker på at det også helt klart var en rigging mot Trump, og er derfor svært bra da den balanserer opp mye av de urettmessige beskyldningene mot høyre-siden, og som også er litt for ensidig her inne. Det var mye snusk på venstresiden også. Mer vil komme for dagen etterhvert. Trump er altså rasist som ikke vil ha fri flyt av narkotika og innvandrere

Trump er altså rasist som ikke vil ha fri flyt av narkotika og innvandrere  At BLM også får støtte her inne sier vel litt om hvor farlig tankegangen er her

At BLM også får støtte her inne sier vel litt om hvor farlig tankegangen er her  Selv Israel får oppleve hatet her inne der de sitter i flertall og håner folk som ikke har samme meninger.

Selv Israel får oppleve hatet her inne der de sitter i flertall og håner folk som ikke har samme meninger.

Nei nå er det bare og vente på når Biden setter igang nedslakting av uskyldige i midtøsten som folk her inne støtter så blir det nok bra med en liten dose BLM vold og terror

"This isn't right," Pauli is supposed to have said of a student's physics paper. "It's not even wrong."Synes det er litt trist at alle som er mot deg her inne ikke kommer med annet enn løgn ig de klager på alternativ media Trump er altså rasist som ikke vil ha fri flyt av narkotika og innvandrere

Trump er altså rasist som ikke vil ha fri flyt av narkotika og innvandrere  At BLM også får støtte her inne sier vel litt om hvor farlig tankegangen er her

At BLM også får støtte her inne sier vel litt om hvor farlig tankegangen er her  Selv Israel får oppleve hatet her inne der de sitter i flertall og håner folk som ikke har samme meninger.

Selv Israel får oppleve hatet her inne der de sitter i flertall og håner folk som ikke har samme meninger.

Nei nå er det bare og vente på når Biden setter igang nedslakting av uskyldige i midtøsten som folk her inne støtter så blir det nok bra med en liten dose BLM vold og terrorJa, du har en del poenger der amason !

Har også merket meg en del vedr måten det argumenteres på:

- Hvis jeg poster et innlegg mye mye som er bra, som de venstrevridde får litt problemer med eller frykter at andre skal lese, er man raskt ute og poster lange nye innlegg, så mitt drukner.

- Man går bare etter det man skal rakke ned på. Når jeg trekker frem andre ting som de virkelig burde reflektere over, forbigås det hurtig og stille.

- Stiller spm hele tiden for å få den som skriver noe til å virke dum/for lite belest osv. når selve saken ikke går på mengde kunnskap, men enkel sunn fornuft... Tankegangen er litt som at om du ikke har lest nok så kan du umulig forstå sammenhenger.

Edit: Jeg sml sosialisme med narkotika. Man blir forgiftet, hekta og er et helvete å komme ut av. Man trenger å avruses.Sist redigert:Jaja. Sammenligner for min del heller trumpkapitalisme med rus.

Regner du høyrefolk som sosialister også?Edit: Jeg sml sosialisme med narkotika. Man blir forgiftet, hekta og er et helvete å komme ut av. Man trenger å avruses.

Ja, det er et spørsmål, men det er oppriktig ment.Bare noen generelle tanker her om diskusjonsformen som noen på forumet her har

- De sier ikke hva de egentlig mener, men kommer med vage antydninger

- De kritiserer aldri enkeltpersoner, men generaliserer der de heller burde svart direkte på kritikk

- De tror at alle som ikke er 100% enige, har rottet seg sammen mot seg

- De misliker å bli motsagt

- De tror de blir hetset når de blir tatt i å ha misforstått og/eller løyet om noe

- De er ute av stand til å vurdere om det er de selv som tar feil

- De tror at jo mer motstand de får, jo rettere har de

Dette er bare noen helt generelle tanker jeg har gjort meg etter å ha diskutert her på forumet litt.Regner du høyrefolk som sosialister også?

Alt til venstre for Djengis Khan er sosialisterTrump sammenlignet seg med Jesus!

Er stor forskjell på å være berømt og å være beryktet for jeg håpe. Hvem av herrene som er hva er kanskje en smakssak?

Trump is winning election lawsuits, in case you haven't heard - LifeSite

Trump has won two-thirds of the cases that have been adjudicated by the courts. www.lifesitenews.com

www.lifesitenews.com

"... of the 80 total lawsuits, 34 have either been withdrawn, consolidated with other suits, or dismissed due to legal technicalities such as lack of standing, timing, or jurisdiction. Those judges who dismissed suits never heard the actual evidence of election irregularities and/or fraud, since they did not allow it to be presented in their courtrooms.... Of the 46 remaining lawsuits, 25 cases are still ongoing, so that the winner and loser of these cases is yet to be determined..."

Forresten, grunnen til at jeg stiller en del spørsmål i din retning er at du ser ut til å være langt mer skrivefør enn visse andre her inne, og da vil jeg gjerne prøve å forstå hvordan i h..e du kommer frem til en del av disse standpunktene. De linkene du poster har så langt stort sett bare vært oppramsede påstander eller (som nå sist) sagt noe i retning av det motsatte av hva du ser ut til å tro.- Stiller spm hele tiden for å få den som skriver noe til å virke dum/for lite belest osv. når selve saken ikke går på mengde kunnskap, men enkel sunn fornuft... Tankegangen er litt som at om du ikke har lest nok så kan du umulig forstå sammenhenger.

Mellom linjene i det du skriver mener jeg å ha forstått at du tidligere hadde politiske standpunkter langt ut på venstre fløy, men har nå gjennomgått enslags omvendelse eller oppdagelse som nå gjør at du befinner deg på aller ytterste høyre fløy. Er det riktig forstått?Sist redigert:

Det viktige er vel hvilke saker/kamper man vinner.

Trump is winning election lawsuits, in case you haven't heard - LifeSite

Trump has won two-thirds of the cases that have been adjudicated by the courts. www.lifesitenews.com

www.lifesitenews.com

"... of the 80 total lawsuits, 34 have either been withdrawn, consolidated with other suits, or dismissed due to legal technicalities such as lack of standing, timing, or jurisdiction. Those judges who dismissed suits never heard the actual evidence of election irregularities and/or fraud, since they did not allow it to be presented in their courtrooms.... Of the 46 remaining lawsuits, 25 cases are still ongoing, so that the winner and loser of these cases is yet to be determined..."

Tiden feller dommen.^

^

eneste vettuge da er jo å gå lenger til venstre, så du slipper mørket- Ble medlem

- 23.03.2006

- Innlegg

- 19.948

- Antall liker

- 10.456

KrF?Stemmer sånn noenlunde, og ellers takk. Men jeg var ikke veldig langt ut på venstre fløy, men i sentrum av den.

Sant nok.Det viktige er vel hvilke saker/kamper man vinner.

Tiden feller dommen.

eneste vettuge da er jo å gå lenger til venstre, så du slipper mørket

Aldri hatt veldig sansen for KrF. Langt tilbake stemte jeg Ap og H litt om hverandre. Etter hvert mest H, så FrP... litt lengre prosess.Trumps regime har resultert i en økt rekruttering på venstresiden. Han er sin verste fiende. Plager meg ikke i det hele tatt

Angående alle Trumps rettssaker: Han har vunnet en, 602 MD 2020, hvor noen stemmer i PA ble satt til side i påvente av nærmere gjennomgang. De hadde ikke blitt talt med i resultatene, så det endret ikke en eneste stemme. Ellers tror jeg bestemt han har tapt eller trukket alle. At saken avvises som grunnløs uten realitetsbehandling regnes ikke som å vinne. Har du eksempler på saker han har vunnet?"... of the 80 total lawsuits, 34 have either been withdrawn, consolidated with other suits, or dismissed due to legal technicalities such as lack of standing, timing, or jurisdiction. Those judges who dismissed suits never heard the actual evidence of election irregularities and/or fraud, since they did not allow it to be presented in their courtrooms.... Of the 46 remaining lawsuits, 25 cases are still ongoing, so that the winner and loser of these cases is yet to be determined..."

Det er ikke så himla vanskelig å få en oversikt som den artikkelen vil ha det til heller:

Ballotpedia's 2020 Election Help Desk: Tracking election disputes, lawsuits, and recounts

Ballotpedia: The Encyclopedia of American Politicsballotpedia.org

Sist redigert:

helt klassisk forfallshistorie, altsåAldri hatt veldig sansen for KrF. Langt tilbake stemte jeg Ap og H litt om hverandre. Etter hvert mest H, så FrP... litt lengre prosess.- Ble medlem

- 23.03.2006

- Innlegg

- 19.948

- Antall liker

- 10.456

Campaign Life Coalition - Wikipedia

Trump is winning election lawsuits, in case you haven't heard - LifeSite

Trump has won two-thirds of the cases that have been adjudicated by the courts. www.lifesitenews.com

www.lifesitenews.com

"... of the 80 total lawsuits, 34 have either been withdrawn, consolidated with other suits, or dismissed due to legal technicalities such as lack of standing, timing, or jurisdiction. Those judges who dismissed suits never heard the actual evidence of election irregularities and/or fraud, since they did not allow it to be presented in their courtrooms.... Of the 46 remaining lawsuits, 25 cases are still ongoing, so that the winner and loser of these cases is yet to be determined..."Bor godt, spiser godt og ikke minst har jeg et respektabelt lydanlegg. Hadde jeg vært utsatt for amerikanske forhold hadde jeg kanskje bare kunnet finansiere våpen.

Jaja. Selv gikk jeg Rød Ungdoms studiesirkel i marxisme da jeg var leder i den lokale Unge Høyre-foreningen. De visste godt hjem jeg var, så det ble tildels livlige diskusjoner. Men hvis man først har en motstander skader det aldri å forstå hvordan de tenker. Vel investert tid.Stemmer sånn noenlunde, og ellers takk. Men jeg var ikke veldig langt ut på venstre fløy, men i sentrum av den.Bodde i Sverige på 70 tallet, og da fikk studenter og andre ubemidlede støtte til å skaffe instrumenter og øvningslokale.

Neppe vært en realitet om sverigedemokratene hadde formet Sverige

Ps. Det vokste fram en sterk musikkbevegelse!- Ble medlem

- 23.03.2006

- Innlegg

- 19.948

- Antall liker

- 10.456

Du likte bedre de frigjorte, BH-løse marxistiske pikene enn de snerpete Høyrepikene, du.Jaja. Selv gikk jeg Rød Ungdoms studiesirkel i marxisme da jeg var leder i den lokale Unge Høyre-foreningen. De visste godt hjem jeg var, så det ble tildels livlige diskusjoner. Men hvis man først har en motstander skader det aldri å forstå hvordan de tenker. Vel investert tid.

I tillegg til frigjorte damer fikke jeg penger til trommesett med studiesirkel systemet som folkhemmet skapte. Alle skulle med.Du likte bedre de frigjorte, BH-løse marxistiske pikene enn de snerpete Høyrepikene, du.

Det er nøyaktig hva Trump, Giuliani og den gjengen ønsker at du skal tro.

Trump is winning election lawsuits, in case you haven't heard - LifeSite

Trump has won two-thirds of the cases that have been adjudicated by the courts. www.lifesitenews.com

www.lifesitenews.com

"... of the 80 total lawsuits, 34 have either been withdrawn, consolidated with other suits, or dismissed due to legal technicalities such as lack of standing, timing, or jurisdiction. Those judges who dismissed suits never heard the actual evidence of election irregularities and/or fraud, since they did not allow it to be presented in their courtrooms.... Of the 46 remaining lawsuits, 25 cases are still ongoing, so that the winner and loser of these cases is yet to be determined..."

FYI så har disse sakene blitt stoppet fordi saksøkerne ikke har hatt noen beviser å føre.- Ble medlem

- 28.09.2016

- Innlegg

- 11.576

- Antall liker

- 11.536

Frp med andre ord?Stemmer sånn noenlunde, og ellers takk. Men jeg var ikke veldig langt ut på venstre fløy, men i sentrum av den.

Giuliani er den eneste mannen som får Trump til å virke sympatisk! Vi slapp unna med livet i beholdDet er nøyaktig hva Trump, Giuliani og den gjengen ønsker at du skal tro.

FYI så har disse sakene blitt stoppet fordi saksøkerne ikke har hatt noen beviser å føre.

-

Laster inn…

Diskusjonstråd Se tråd i gallerivisning

-

-

Laster inn…