As Donald Trump almost blew up the trans-Atlantic alliance last week, the usual hand-wringers who have bemoaned every step in the president’s rise were out in force, as incandescently eloquent and as irredeemably futile as ever. Mr. Trump’s MAGA-world supporters also were in full cry, hailing the daring originality of a man whose supposed 3-D chess moves break all the rules.

What the cheerleaders and the mourners alike missed is that Mr. Trump’s Russia policy is, in many respects, mainstream. Like Gerhard Schröder and Angela Merkel, the president wants to look past political and ideological differences with Moscow to develop mutually beneficial economic links. Like Barack Obama, he believes that antagonism between the U.S. and Russia is an anachronistic echo of the Cold War. Like Joe Biden, Mr. Trump wants to park Russia: to avoid the pain, difficulty and expense of confronting Moscow by establishing some kind of working arrangement with it.

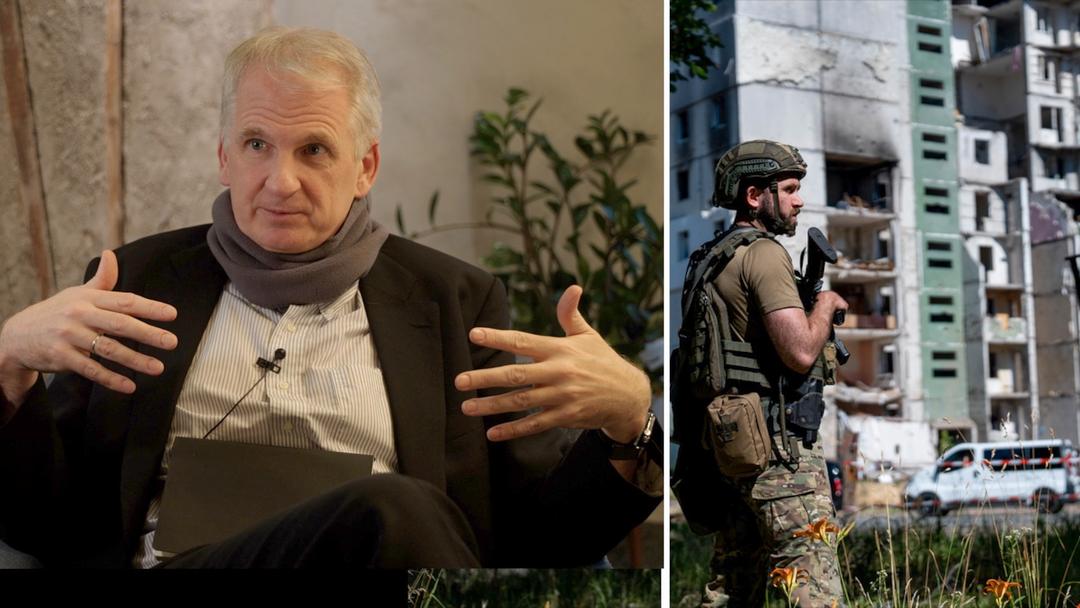

The substance of the Trump administration’s proposals to Russia—accepting territorial gains along with providing inadequate security assistance to Ukraine—is where the Biden administration and its chief European allies would likely have ended up. This is how George W. Bush, Mr. Obama, Ms. Merkel and Mr. Biden treated Russia’s actions against Georgia during and after 2008 and its 2014 attack on Ukraine.

But there are differences between the old and the new Russia policies. While his predecessors used harsh anti-Russian rhetoric and symbolic sanctions to disguise their supine pragmatism to their supporters and possibly to themselves, Mr. Trump wants to send Vladimir Putin candy and flowers. For Mr. Trump, treating Mr. Putin with “respect”—as Tony Soprano would put it—is the way to a stable, businesslike relationship with the Russians. If this approach isn’t a comprehensive answer to America’s Russia problem, it isn’t entirely wrong. If you want someone to park on your street, don’t throw dog poop at their car.

There is more. In the Trump view, European countries haven’t merely stiff-armed American requests to increase defense spending. Led by Germany, they have seized every opportunity to trade with Russia, even when that trade weakened European security and strengthened Moscow. The old American policy locked the U.S. into the ridiculous posture of begging Berlin to stop undermining its own security by relying on Russian energy.

Team Trump wants to flip this dynamic. Since Russia is closer to Germany and presumably a greater threat to it than to the U.S., let Germany take on the burden of its security, while the U.S. establishes close commercial relations with a country that doesn’t directly threaten us. In a properly run universe, Team Trump feels, Germany should be begging the U.S. to avoid trade deals with Russia that undermine European security, not the other way around.

Mr. Trump’s course is disruptive and risky, but it is internally consistent. Offering Russia an economic partnership with the U.S., dropping the ideological campaign against it and reducing America’s role in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization can all be seen as efforts to achieve the longtime Western goal of neutralizing Russia or even enlisting it against the greater danger posed by Beijing.

The Trump administration’s approach echoes the views then-Commerce Secretary Henry Wallace laid out to President Harry S. Truman in a letter dated July 23, 1946. Joseph Stalin’s distrust of the West, Wallace argued, stems from defensiveness resulting from more than a thousand years of foreign invasion and encroachment. Containing Moscow by building alliances around it would deepen Stalin’s paranoia and increase his hostility. The solution was to win the Kremlin’s trust by withdrawing from contested areas, accepting Soviet proposals to guarantee their security, combating American hostility toward the Soviet system, offering the possibility of a deep economic partnership and promoting bilateral trade.

Diplomat George Kennan, the architect of America’s Cold War containment strategy, spent most of his career calling for American restraint in the Cold War, but he thought Wallace was badly misguided. Kennan argued that stable, businesslike relations with Moscow were possible, but only after Stalin realized that the West could and would successfully resist his expansionary efforts. Détente could follow containment but could never replace it.

There are clear risks to Mr. Trump’s Wallace-inflected policy. Europeans, including some historically very pro-American voices, won’t soon forgive or forget Team Trump’s affronts to their dignity and threats to their security. Mr. Putin may well pocket all the concessions Washington offers him and then double down on both his alliance with China and his aggression in Ukraine. Japan sees Mr. Trump’s cavalier attitude toward longstanding allies in Europe as a threat to its own security.

Henry Wallace ultimately came to regret his naiveté of the 1940s. We shall see how President Trump ends up.