Krugman i Financial Times:

More than four years after the financial crisis began, the world’s major advanced economies remain deeply depressed, in a scene all too reminiscent of the 1930s. The reason is simple: we are relying on the same ideas that governed policy during that decade. These ideas, long since disproved, involve profound errors both about the causes of the crisis, its nature and the appropriate response.

These ideas have taken root in the public consciousness, providing support for the excessive austerity of fiscal policies in many countries. So the time is ripe for a manifesto in which mainstream economists offer the public a more evidence-based analysis of our problems.

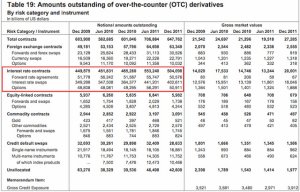

The causes. Many policy makers insist that the crisis was caused by irresponsible public borrowing. With very few exceptions – such as Greece – this is false. Instead, the conditions for the crisis were created by excessive private sector borrowing and lending, including by over-leveraged banks. The bursting of this bubble led to large falls in output and thus in tax revenue. Today’s government deficits are a consequence of the crisis, not a cause.

The nature of the crisis. When property bubbles burst on both sides of the Atlantic, many parts of the private sector slashed spending in an attempt to pay down past debts. This was a rational response on the part of individuals, but has proved to be collectively self-defeating, because one person’s spending is another person’s income. The result of the spending collapse has been an economic depression that has worsened the public debt.

The appropriate response. At a time when the private sector is engaged in a collective effort to spend less, public policy should act as a stabilising force, attempting to sustain spending. At the very least, we should not be making things worse with big cuts in government spending or big increases in tax rates on ordinary people.

The big mistake. After responding well in the first, acute phase of the crisis, policy took a wrong turn – focusing on government deficits and arguing that the public sector should attempt to reduce its debts in tandem with the private sector. Instead of playing a stabilising role, fiscal policy has ended up reinforcing the damping effects of private-sector spending cuts.

In the face of a less severe shock, monetary policy could take up the slack. But with interest rates close to zero, monetary policy – while it should do all it can – cannot do the whole job. There must of course be a medium-term plan for reducing the government deficit. But if this is too front-loaded it can easily be self-defeating by aborting the recovery. A key priority is to reduce unemployment, before it becomes endemic, making recovery and future deficit reduction even more difficult.

How do those who support the existing approach respond to ours? They typically use two arguments.

The confidence argument. Their first argument is that government deficits will raise interest rates and thus prevent recovery. By contrast, austerity will increase confidence and encourage recovery.

But there is no evidence in favour of this argument. Despite exceptionally high deficits, interest rates are unprecedentedly low in all major countries where there is a normally functioning central bank. Interest rates are only high in some eurozone countries, because the European Central Bank is not allowed to act as lender of last resort to the government. Elsewhere the central bank can always, if needed, fund the deficit, leaving the bond market unaffected.

Experience includes no relevant case where budget cuts have actually generated increased economic activity. The International Monetary Fund has studied 173 cases of budget cuts in individual countries and found that the consistent result is economic contraction. That is what is happening: the countries with the biggest budget cuts have experienced the biggest falls in output.

For the truth, as we can now see, is that budget cuts do not inspire business confidence. Companies will only invest when they can foresee enough customers with enough income to spend. Austerity discourages investment.

The structural argument. A second argument against expanding demand is that output is in fact constrained on the supply side – by structural imbalances. If this theory were right, however, at least some parts of our economies ought to be at full stretch, and so should some occupations. But in most countries that is not the case. So the problem must be a general lack of spending and demand.

In the 1930s the same structural argument was used against proactive spending policies in the US. But as spending rose between 1940 and 1942, output rose by 20 per cent. So the problem in the 1930s, as now, was a shortage of demand, not of supply.

As a result of their mistaken ideas, many western policy makers are inflicting massive suffering on their peoples. But the ideas they espouse about how to handle recessions were rejected by nearly all economists after the disasters of the 1930s. It is tragic that in recent years the old ideas have again taken root.

The best policies will differ between countries and will require debate. But they must be based on a correct analysis of the problem. We therefore urge all economists and others who agree with the broad thrust of this manifesto for economic sense to register their agreement online and to publicly argue the case for a sounder approach. The whole world suffers when men and women are silent about what they know is wrong.